On the morning of September 6, 2013, 275 canoes and nearly 700 paddlers converged at Old Forge Beach in New York’s Adirondack Park. Eager anticipation lingered in the air as canoers snacked and stretched and prepped their boats for the Adirondack Canoe Classic, a 90-mile, three-day race from Old Forge to Saranac Lake.

Bobbing near the starting line in a C2 (two-person canoe), I perched on the edge of my bow seat and held my bare arms to my chest, shivering from nerves and the morning chill. Silvery tendrils of fog rose from the water. I turned to Ally Kontra, my teammate and boat captain: “Remind me again why we signed up for this?”

A gray-bearded man wearing a baseball cap regarded us from a canoe to our right. He raised a scruffy eyebrow. “This your first 90?”

Ally and I were part of a team from Hamilton College that featured 22 paddlers and six boats of various sizes and capacities. Eleven pit crew members – our drivers, chefs, cheerleaders, and support squad – filled out the team.

The paddlers that surrounded us were of every age: a few teenagers and college students, as well as experienced canoe racers and septuagenarians. Bearded Adirondack natives comprised a substantial proportion, but some hailed from as far as France and Hawaii.

Race organizer Brian McDonnell issued instructions from the dock, and at the call we dug our paddles into the black water and our boat lurched forward. Around us, the lake churned as canoes, bumping and jostling, hurried toward open water. A cheer rose from spectators on the beach. We were off.

The Canoe Classic was conceived in the late winter of 1982. Bill Hulshoff, who now acts as head timer, came up with the idea during a Saranac Lake Chamber of Commerce meeting. “We were sitting around wondering what kind of event we could do in the summer, and I said ‘You can pretty much paddle from Old Forge to Saranac Lake.’ After a few coffees, it sounded like a good idea.”

Paddlers have clearly agreed: nearly 40 have completed the course more than 20 times, and one of them, Ray Morris, has paddled all 31 years.

In 1999, Brian and Grace McDonnell assumed responsibility for the eventfrom the Saranac Chamber. Together, the couple runs Mac’s Canoe Livery and the Adirondack Watershed Alliance (AWA), which promotes water sports and stewardship on the waterways of the Adirondacks.

“In the 15 years we’ve run it, we’ve been full every year,” Grace McDonnell said, a note of pride lacing her voice. She added that more of the larger boats – C4s and war canoes – have increased the total number of participants.

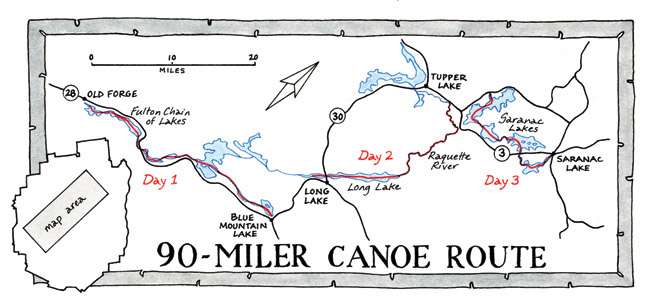

The race follows the “canoe highway” of the Adirondacks, the same route traveled for centuries by Native Americans, woodsmen, and settlers. Now the route is discontinuous, with three timed legs.

“It’s doing something you love for three days in a beautiful place,” she said, explaining the reasons the racers return year after year. “It’s a real community.”

Day 1

Out on the water, we made our way along an inlet toward First Lake in the Fulton Chain of Lakes. It would be the first of 11 lakes – 35 miles – to be covered that day. After a mile or so, our rhythm steadied to about 75 strokes a minute. Every ten or fifteen strokes, Ally would call out a short “Hut!” and we’d switch the paddle to the opposite side of the boat. With practice, we found the switch caused barely a hitch in our tempo; if we timed it right, our paddles swung over the boat and dipped into the surface of the water with mesmerizing synchrony.

The canoes thinned and some pulled out ahead, shrinking to dark, blurred silhouettes in the fog ahead. We took our first snack break after an hour, pausing one at a time for a rushed cup of applesauce. Earlier that morning, we had duct-taped a battalion of protein bars, bite-sized Snickers, and applesauce packets to the sides of the boat in easily-accessible rows. We had been advised to eat every half-hour, to ensure we’d consume at least half the calories we’d burn.

“This isn’t so bad,” I told Ally. “Only seven more hours to go.”

We passed through First Lake and Second, then Third and Fourth. The canoe cut through the polished surface of the water, and, other than the gradual shifting of the landscape, our progress was hardly discernible.

The end of Fifth Lake marked our first of eight portages. (Though Andrew Jillings, Hamilton’s director of outdoor leadership and war canoe captain, had informed us that, “if you’re cool and local, you call them carries.”)

The canoe’s keel grated against the sand, and we leapt onto the muddy beach. We hoisted the canoe onto our shoulders and marched off up the dirt path, stooping slightly under the weight. The paddles and food rattled in the boat; as we moved from the trail onto a paved road, Hamilton pit crew members cheered us on. The canoe seemed to accumulate weight and bulk as we walked, and we were glad to clamber back into the boat at Sixth Lake.

Chris Woodward, who has volunteered with the Canoe Classic for over twenty years and raced in it three times, described the route as “the central waterway from south to north for, oh, about 10,000 years.” Woodward, who has spent most of his life on and near these waters, builds and repairs Adirondack guideboats at his shop in Saranac Lake.

Before the settlers staked a claim on the rugged land, he explained, the Native Americans were making use of the routes. The Mohawk hunted and fished in this area, spending summers up on the St. Lawrence and traveling along the Adirondack waterways to their wintering grounds on the Mohawk River.

Settlers and woodsmen made their way into the area starting in the 1840s, and until the railroads came through the region in the 1870s, rivers and lakes were the primary mode of transport. “They went by water as much as possible,” Woodward said. “It’s pretty hard going otherwise.”

We continued though the legendary Brown’s Tract, an infuriatingly narrow sequence of hairpin turns, where any wrong maneuver left the canoe lodged amongst the water lilies. Perhaps twenty canoes glided past as we thrashed in the shallows.

The Brown of Brown’s Tract, Woodward said, was a distant relation of the namesake of Brown University in Rhode Island. “He was given a tract of land. He was going to make a utopian community, but it has pretty thin, acidic soils, so it didn’t go for long,” he explained.

When we finally cleared Brown’s Tract, confident that the end was a mere half-hour away, Ally and I envisioned the finish, rejoicing in the food, the warm clothes, the soft grass. We didn’t catch sight of the final buoys for another two hours, however, long after our excitement had lapsed into frustration, then weary and silent resignation. At some point, I did the math and figured that by the end of the weekend, I would have paddled nearly 100,000 strokes.

Day One finally ended at a grassy beach in Blue Mountain State Park. The pit crew waded out to pull us up, and I collapsed on shore in utter relief and fatigue.

That night, we stayed at a nearby campground, setting up a small metropolis of tents spread across several sites. We gathered at picnic tables to eat, emptying our bowls again and again. Exhaustion and a sense of satisfied accomplishment lent an air of joviality to the scene.

When darkness fell, Andrew, our leader, retrieved his paddlers’ map and laid it out on the pine needles. The team circled around and watched as, by headlamp, he outlined the route for the following day with a stick, describing wind direction, landmarks to watch for, and the terrain of each carry.

And then there was the perpetual retelling of the accumulated 90-Miler folklore and stories. “You can’t say you’ve done the 90 ’till you’ve peed in the boat,” a two-time racer informed the group. “While still keeping pace.”

Day 2

On Saturday morning, I awoke to an ache lodged deeply in every muscle. Fog still lingered as we located our boat amongst the golden, sprawling array. The start line lay at the bottom of the aptly named Long Lake.

As we set off, the canoes seemed caught up in the vastness of the surroundings – the forested swells that rose from rocky black shores, the arcing swatches of light that reflected off the wakes of other boats, the sky that changed from pastels at the horizon to azure overhead.

As they passed, canoers greeted or encouraged one other, and I grew to recognize many of the boats, though I never learned a single name.

“You girls must be experts at this!” one man called to us from his solo canoe.

“Basically,” I replied, with a shrug and a half-smile. “We’ve been doing this at least a week-and-a-half.”

It wasn’t much of an understatement. Ally and I had practiced together just nine times since we had arrived on campus in August. We had learned the short, vertical stroke that would permit a pace of 70 strokes a minute, lifting the blade from the water before it reached the waist. The captains gradually learned to maneuver their vessels, and in the bow, I learned to keep a rhythmic pace. We learned to gauge each other’s preferences and quirks, adjusting to the boat’s steering and balance.

After two-and-a-half hours on Long Lake, we merged onto Raquette River. The canoes thinned to single file, following the meandering oxbows.

After each curve stretched another curve. Cedar, spruce, and beech crowded along the banks and arched over the water, thick forests interspersed with reedy, windswept marshes. Motion could hardly be detected in the unhurried current, and the water faithfully reflected the banks on each side.

We pulled up to the bank for the sole carry of the day. A kayaker warned us that, at 1.25 miles, it was the “worst part of the race.”

Ally and I hoisted the canoe up stone steps, joining the procession of paddlers maneuvering their way up nearly half-a-mile of steep, rocky trail. Partway up, we heaved the canoe onto our shoulders, and the sharp ridgeline of the hull dug into my already bruised collarbone. The waterbottles, food, and paddles shifted toward the stern as we clambered and stumbled uphill, and Ally let out a small groan. “Slow down a little.” We descended, breathing hard, and eventually lurched our way onto the beach, where a volunteer held out paper cups of water and a platter of Twix bars.

It was a relief to paddle then, and we set off for the last twelve or thirteen miles at a brisk pace.

We spent the night at Fish Creek Campground, a few campsites away from where we would start the following day. We ate until we were bloated and collapsed into our sleeping bags before 9 o’clock.

Day 3

On Day Three, we awoke early, to the same persistently brilliant sky. I taped my blistered fingers and shoveled down two packets of instant oatmeal and a peanut butter sandwich, before cleaning my bowl with green tea.

It was the shortest of the three days, 25 miles to the end of Lower Saranac Lake. It would take, we were told, no longer than six hours.

At the start, wave two moved en masse into the first of the three Saranac Lakes. Soon a northeasterly wind picked up, shoving the waves insolently against our canoe. Our exertions felt fruitless; the far bank never seemed to grow closer and the canoe paid no heed to our frantic efforts to keep it on its course. On shore, families wrapped themselves in blankets to watch from their camp docks. Some rang cow bells and shouted encouragement as the canoes slipped by.

Two hours into the day, the eight-person war canoes caught up to us, followed by a steady procession of C4s. Some passed singing; others we’d recognize by their distinctive canoe decorations, bumper stickers, or figureheads. Two paddlers, who later claimed victory in the tandem guideboat division, wore coonskin caps and called themselves Daniel Boone and Davy Crocket.

The guideboat, an oval-bottomed boat pointed on both ends, evolved as the versatile and ubiquitous “pick-up truck” of the Adirondacks in the mid-nineteenth century. Woodsmen needed a boat sturdy enough to paddle to town or to transport supplies, and light enough to carry between waterways. The boat typically has overlapping slats along the sides and is rowed like a rowboat, with space for a second paddler or passenger in back.

In the late 1800s, when tourism picked up in the Adirondacks, wealthy families took the train up from downstate and stayed at hotels along the lakes. The guideboats earned their name during this period, as locals ferried hotel patrons to their lodging or gave tours to hunting and fishing sites.

Once, on the choppy water of some interchangeable lake, I called out to the coon-skinned pair, complimenting their headwear. They laughed, noting that the caps weren’t real; they had bought them at a gas station on the drive down to Old Forge.

We struggled through three carries that day and navigated our way up a meandering river, edged with ochre tamaracks. Sometimes Ally and I talked – about our favorite foods, the paddlers who passed us, or about ourselves. We learned to estimate our progress by the number of snacks we had consumed – an applesauce, two jellybeans, and a bite of Clif Bar since the last carry.

“Look at you young whippersnappers!” a canoe of four women called, as they paddled past in perfect uniformity. “We’re old enough to be your grandmothers!”

We portaged over a lock, deposited the canoe back in the water, and continued. Soon, we entered Lower Saranac Lake and the scene spread out before us: “the best view on the route,” Andrew had promised. Sure enough, the Adirondacks stood in all their splendor, a collage of greens framed by the sky above and reflected in the water below.

The final hours of the race condensed into a blur of exertion and excitement. At last, we rounded the final corner, and as we passed the buoys our time rang out over the speakers: 19:40:45. I raised my paddle over my head with a broad grin.

Hands pulled me onto the boat launch, and I turned to throw my arms around Ally. “We did it!” A flurry of awards and happiness and food followed. The celebration reflected the deeply entrenched culture of the 90-Miler: the solidarity of accomplishment, an over-abundance of chocolate milk, lively stories that grew larger the more times they were told.

In the midst of the picnic blankets near the beach, I stretched wearily out on the grass and let the sun warm my hair. Nearby were Larry Sweeney, of Suffield, Connecticut, and canoe partner Brian Finn, who’ve paddled this race 28 times. He and Finn live several hours apart, and they can’t train like they used to. Still, they have no plans to stop.

“I’m going to keep doing it until we don’t make the cut-off time and they kick us out,” Sweeney said.

Discussion *