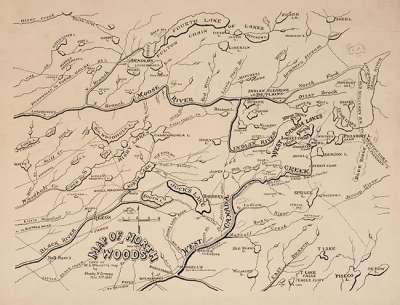

This is a story about Adirondack hermits, but the place and time in which it unfolds are as big a part of the tale as anything else. It was the late 1800s, see, and everything in America was changing. Our nation’s population was expanding at an astounding pace – growing at a rate of 25 percent per decade. The West had been settled, the buffalo slaughtered, the Native American resistance largely quelled. The Civil War had fueled a manufacturing boom, and we were transforming from an agrarian economy to an industrial one.

New York was changing as rapidly as any part of the country. Seventy-five percent of the state had been cleared of forest, with much of what remained clustered in the Adirondacks, where the terrain made settlement difficult. Even in the Adirondacks, though, the forests had been pecked away for a century; first to go were the mature white pine and red spruce, then the hemlock for tanbark, then smaller stuff for the hungry pulp mills downriver. The state had sold the land for pennies an acre to pay back Revolutionary War debts, and after the early timber barons extracted what value they could from the timber many simply abandoned their properties, rather than continue to pay taxes, in some cases leaving lumber camps standing for the first squatters to come along.

And come they did. A report by the New York Conservation Commission indicated that there were some 800 individuals of various means living on state land around 1915, to say nothing of those camped on private timberland without benefit of a title. The squatters’ circumstances varied, but a healthy number were woodsmen who just didn’t fit in with the Industrial Age. Here, amidst millions of acres of open space, in a forest that teemed with deer, small game, and furbearers, these pioneers went about living a life that, for the most part, didn’t exist anymore.

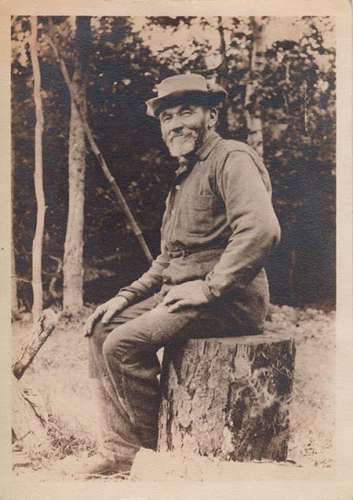

French Louie

In the 1880s, word began filtering out of the woods about a mysterious person living in the upper reaches of West Canada Creek in Hamilton County. Only a few of the more adventuresome trappers and woodsmen had encountered this man; they described him as being somewhat short, having a heavy beard and more than a few patches on his wool trousers.

Folks in Newton Corners (Speculator today) knew him as French Louie, although his real name was Louis Seymour. Louie came to New York State as a boy in the 1850s, arriving from the Dog River area north of Ottawa, Canada. He worked several jobs around the state, including as a mule driver on the Erie Canal and as a circus hand near Saratoga, before moving to the Adirondacks and working in the lumber woods.

Around 1880, after trapping the area with a couple of men from Newton Corners, he decided to quit logging and build a cabin at West Canada Lake, about 12 miles back from the old wagon road north of the Corners. It would have been difficult to find a more remote section.

In the surrounding woods, Louis set about making a series of trap line camps – around a dozen, all told – for which he became famous. Some of them were log lean-tos, usually built within a foot or two of a large flat rock to reflect heat and light into the structure. His more elaborate camps had split plank floors and “scoops” for roofs. These were halves of logs that were hewed out in a trough fashion and placed overlapping on the roof to drain rain and snowmelt. One overnight camp on Otter Brook consisted of a large, hollow yellow birch log with a door on the front. According to an account in the book Adirondack French Louie by Harvey Dunham, if Louie didn’t want someone around one of his camps he’d warn them, “Ah got trap set for bear.”

Despite the remote location, Louie always seemed to keep his larder well stocked. His garden, well composted with fish and trap line leavings, was said to grow rhubarb as thick as a person’s arm. My father, Charlie Wharton, stayed in Louie’s camp with Ed Brooks, a lumberman from Speculator, when they were cruising timber for Union Bag and Paper Company. Brooks recalled that one Sunday he’d stopped to visit with Louie to see if the old hermit could point him toward a good place to catch a couple trout. Brooks had found a few holes in the ice, but the fish weren’t biting. Louie threw open a side door to the cabin, and Ed saw frozen brook trout and lake trout stacked up chest high against one wall. “Help yourself,” said Louie. This story was later recounted in Tales from an Adirondack County, by Ted Aber and Stella King.

Shallow and weedy Mud Lake was a favorite place for jacking deer, which Louis did from his guide boat equipped with a Ferguson jack light. He also ran deer with dogs for “sports” from the city. Around this time, state officials were enacting the first fish and game laws in the region. The first bag limit, three deer per season, was enacted in 1896; jacking was outlawed a year later. The old ways died hard in the backwoods, and Louis was arrested for illegal venison on one occasion and had to make the long hike out of the woods to court, but a jury of his peers – old-timers like himself – found him not guilty.

Louis made a twice-annual pilgrimage to town, and people at Newton Corners knew that he’d returned by the owl hoots and wolf calls he made as he entered the village. Kids would follow along and try to get him to mimic animal calls, and he’d oblige; he also tossed small coins out to them. He would then proceed to indulge himself in drowning his six-month thirst at local barrooms. He wouldn’t touch a bottle in the woods, though, knowing very well that you want all your wits about you when handling an axe or bear trap.

Louie died in 1915, the same year the State of New York made it illegal to squat on state land. To honor the local legend, kids in Newton Corners were let out of school and each child placed a small balsam bough in the casket as they passed by. Even today, visitors will occasionally toss a whiskey bottle and a few coins down next to the old hermit’s headstone. It reads, “Erected by Admirers.”

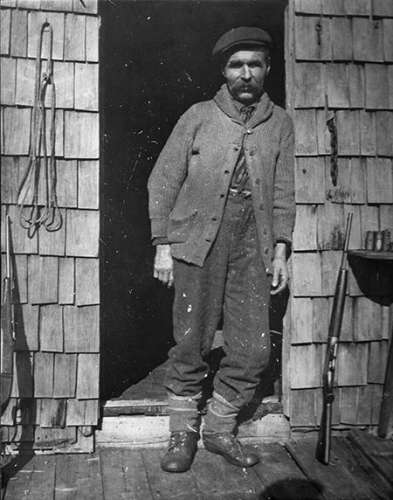

Foxey Brown

Foxey Brown was a railroad man when he came to New York State around 1890 from Boston. In Tales from an Adirondack County, it was reported that he’d gotten into a fracas there and had left the other guy for dead. Brown worked on logging operations around Lake Peasant before settling in the backwoods six miles north of Piseco and about 10 miles southeast of Louis Seymour’s West Canada country.

Foxey, whose real name was David Brennan, was a short individual with a heavy beard and gruff manner of speech. He built himself a little log cabin at the lower end of an old logging flow on Fall Stream, where he lived for about 25 years. He cleared a few acres of land, built a small barn, and kept a few chickens and livestock. Like many other Adirondack hermits, he hunted, trapped, and made shingles, which he sold locally. He had a small spring at the base of a hill where he kept canned goods to prevent them from freezing in the winter.

Trespassers weren’t welcome in his neighborhood, and he would holler out that he would “send lead for sinkers” if they didn’t get moving. He wasn’t fooling, and he did shoot several times at Piseco game protector Charlie Preston. (The two later became friends.) He also claimed to have put a bullet hole through guide Old Man Courtney’s hat – while it was on his head. Foxey mellowed in later years, but most people still kept their distance.

In November 1916, Brown was guiding hunter Carleton Banker when Banker disappeared after being placed on a deer stand. Foxey and another man who was hunting with the pair fired signal shots, but no answering shot was heard. The next day a massive search involving 100 men and bloodhounds began; searchers combed the woods for five days without finding any definitive sign of the missing hunter. Then a heavy snow blanketed the Piseco Mountains and the search was called off.

Many suspected that Brown was responsible for Banker’s death, though there were also reports that the two had been friends. Banker’s body was eventually found miles from where he’d taken his deer stand. In the intervening years, Foxey learned that he’d been tried in absentia and found not guilty of murder in the case, but by then he’d packed up and moved south. What happened to Carleton Banker remains a mystery.

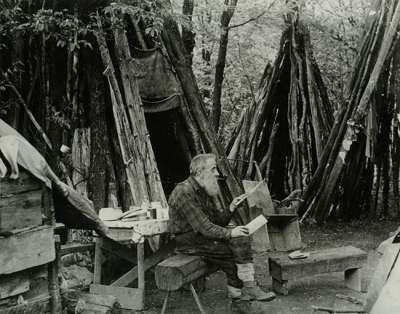

Noah John Rondeau

“There isn’t a more bona fide hermit in the whole United States – including Sharktooth Shoal – than Noah John Rondeau, who has occupied a hole in the woodpile way the hell and gone back in the Adirondack wilderness for 33 years,” wrote New York Conservation Department educator Clayt Seagers in a 1946 edition of Conservationist magazine.

Noah John made his first trip into Cold River in 1902 for the purpose of reconnoitering the hunting and trapping, and for the next two decades made seasonal trips in the fall and spring guiding hunters and fishermen. In 1929, he took up more or less permanent residence in a scenic spot overlooking the Cold River Flow, a location about midway as the crow flies between Lake Placid and Newcomb and surrounded by High Peaks like Panther, Seward, and Santanoni. With materials salvaged from a long-abandoned Santa Clara Lumber Company camp, he built two small huts just tall enough for him to navigate with his five-foot, two-inch frame. One hut was named the Town Hall and the other the Hall of Records. He slept in the Town Hall in the winter but moved to one of his wigwam woodpiles in the summer. The wigwams were 30-foot lengths of pole wood stacked up teepee fashion with the poles notched at two-foot intervals. When he wanted to stoke his fire all he had to do was whack a pole with his axe and he had a length of firewood.

According to his biographer Maitland DeSormo, Rondeau had a dim view of government: big business, welfare, economic and political systems in general “infuriated” him. He had a long-simmering dispute with the Conservation Department that began with a small brush fire they accused him of starting in 1910. He refused to pay the nine dollar fine for damages the state said he had caused. After that, forest rangers were on his case for a long list of infractions, including guiding without a license, illegal venison, and camping and cutting trees on the forest preserve. While Rondeau eventually befriended several forest rangers, he still liked to demonstrate his prowess with a bow to High Peaks hikers by putting an arrow through a diagram of a ranger’s hat. He would shrug it off with, “Too bad,” if he missed a little low. A small sign on his Town Hall camp read, “NO GAME PROTECTORS ALLOWED.”

Noah John was able to scratch out a small garden in the thin mountain soil, and the river and nearby ponds and streams contained brook trout that added to his menu. He noted in his journals – which were written in a sophisticated code he’d made up so “official busybodies” couldn’t read them – that deer were “in excess” in the surrounding territory, so he had a supply of venison for himself and good hunting for the sports he guided. He cooked his flapjacks in rendered bear fat and ate them rolled up with a little syrup. When he was in the area, chief conservation pilot Fred McLane would sometimes buzz the Town Hall and drop off a loaf of bread and bundle of newspapers.

In 1947, the Conservation Department dropped Rondeau a note, asking him to appear at a sportsmen’s show in New York City. The department’s idea was to use him to promote the wild character of the region. Rondeau went along, appearing in a muskrat hat and buckskin suit. He went on to do a series of shows, including one I witnessed firsthand in Amsterdam, New York, later that year.

The Big Blowdown of November 25, 1950, affected over 400,000 acres of Adirondack timber, and the state closed the woods for several years. Rondeau’s hermitage near Cold River was hard hit, and he was unable to return. He found some menial work, which included playing Santa Claus at an Adirondack Christmas theme park, but struggled financially; according to his Wikipedia entry, he eventually went on welfare. His desire when he died was to be buried back in his Cold River bailiwick, but instead he was buried in August 1967 at the North Elba cemetery, within a stone’s throw of a group of his favorite white pines. It marked the end of an era for the Adirondacks.

Discussion *