I’ve assessed spotted owl feuds and wolf re-introductions,” said Dr. William Lynn, an environmental ethics professor at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. “I’ve never, though, seen the anger the cat issue provokes.”

For a century, debates over cat-on-wildlife violence played out in esoteric shadows, a testy but fringe spat with hunters and birders on one side and cat aficionados on the other. It would have stayed that way, but two things happened between World War II and now that embroiled us in the emotive mess Dr. Lynn describes: first, we suburbanized, and then we fell madly in love with housecats while simultaneously doing so with wildlife. According to the American Humane Society, American cat ownership grew from roughly 4 million in 1945 to 85 million today, while in the same time period, birdwatching went from a quirk of wealthy kooks to a national pastime.

While the politics surrounding the issue have grown fractious, most people with an ostensible stake remain ignorant or neutral. Many casual birders have cats themselves, and out in the country farmers still keep barn cats for the same reason Neolithic North Africans first did 10,000 years ago – to kill rodents. Whatever warblers, thrushes, butterflies, and rabbits they snuff on the side – along with all the feral offspring their ramblings produce – usually get tucked into the “That’s just part of nature; what’s the big deal?” file. The same is true for the bulk of presents pet cats leave on their owners’ doorsteps.

But with wildlife facing the grim grab bag of eco-stressors that it is – from climate change to habitat degradation to pollution – domestic felines and what they kill have begun to receive thorough study and more attention recently. The data suggest that in New York and New England alone, cat-kills likely play out several thousand times a day. Early June, say, outside Hartford, Connecticut. Thirty houses went in last fall along a powerline. A chestnut-sided warbler pair didn’t know people were managing the line for early successional cover, but the shrubs were there, so in went their nest. With the houses, though, came something new.

Rotating its ears independently, the calico heard the days-old warbler chicks 40 yards off. Soft-padding here, now there – stopping, listening, homing in – it closed half the distance. Yards away, the female warbler scratched last year’s leaves, then popped up to snatch a tent caterpillar off a white oak in its last act. Having pounced, the cat pinned the fading bird while adjusting its ears, triangulating those persistent cheeps.

“It’s true,” said Megan Washburn, a Massachusetts North Shore cat owner. “We let our lions roam. I know there are complications with that, but it’s part of their make-up. Two of them can’t catch colds, but Maui could support the family.”

A Numbers Game

Fortunately for wildlife, our affection for cats coincides with an equally gushing passion for their prey, particularly birds. Politically, ecologically, socially, and even philosophically, then, we are faced with a dilemma.

“Anything affecting the interface between the human and natural worlds is delicate cloth,” said E. J. Barnes, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based illustrator once ensconced in pointed feral cat tussles in the western part of the state. “If you pick one thread, the whole thing unravels.”

With many once-rural areas of the Northeast facing increasing human populations, the question of boundaries is a fretful one. Cats vex it further, raising questions of what stewardship means, how responsible we are to creatures that don’t directly benefit us, and who decides what those benefits are, all of which aggravate the uneasy if not impossible dispute over distributing animal welfare evenly. Not simple stuff, particularly with cute cats, cute birds, and the people who adore each living side by side.

For now, domestic cats are the lesser worry. Though their take is still worrisome, everything from outdoor cat pens – “catios” – to bells, to de-clawing and other measures have diminished the amount of wildlife they kill. At the heart of the issue, then, are feral cats, though getting a firm grasp on their numbers is difficult.

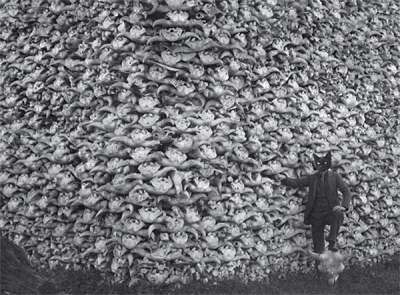

“Nobody knows what’s out there,” said Grant Sizemore, an invasive species specialist for the American Bird Conservancy, which favors culling feral cats. “The Smithsonian study put [the number of feral cats] at 30 to 80 million.”

That 2012 study, conducted by Scott Loss, Tom Will, and Peter Marra from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the Fish and Wildlife Service, touched off much of the current teeth-gnashing. It compiled and analyzed past research on the topic, with its authors eventually concluding that cats kill trainloads more wildlife than was previously thought. The number of projected bird deaths was never small, but correlated with the 30- to 80-million feral cat number and estimates of what the 85 million pet cats kill, the Smithsonian team put bird mortalities at 1.3 to 4 billion per year in the U.S.

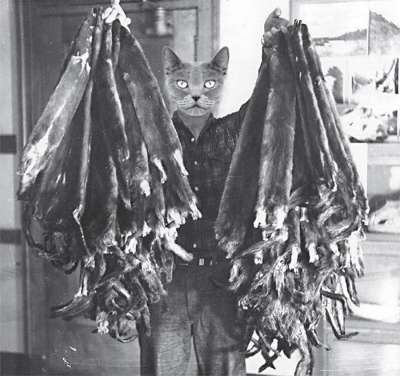

Non-avian deaths, too, range into the stratosphere – 20 billion at most. While this includes non-native house mice and Norway rats, cats are infamously indiscriminate. An ongoing University of Georgia study puts cameras on pet cats. Though two-thirds mostly laze around, the remainder are Ripperesque. Lizards are their most frequent victims in that region, demonstrating that what’s killed is what’s available. In the Northeast, this means the mice and voles (great for humans who want fewer of them in grain bins and kitchen cupboards, not great for weasels, rat-snakes, and screech owls), but also far touchier targets conservation-wise, such as New England cottontails, monarch butterflies, and piping plovers, all endangered or threatened. If it’s snowshoe hare-sized down, it’s game, and cats come to play.

“It’s a shame,” said author Jim Sterba, whose book Nature Wars dedicates a chapter to cat predation. “Few people understand how lethal they are. Each ear is connected to thirty-some muscles, and they’re beyond stealthy. One of the first to sound the alarm was Herbert Stoddard, who studied the impact cats have on bobwhite quail. Cats don’t molest eggs, but he found they could hear them hatching and then move in. It didn’t matter if they’re hungry or not. In the way rodents gnaw to hone teeth, cats hunt to hone their own tools.”

Sizemore echoed this. “Chasing laser lights, pouncing, pawing string balls – all that cuteness indoors is death outside.”

Picking Sides

So what can be done? Many in the wildlife management camp have called for feral cat culls, while the pro-cat side sees Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) as the preferred way to address the issue. TNR volunteers trap ferals at feeding stations, sterilize them, then return them to their roaming ways. It’s touted as a humane approach, yet not all animal welfare organizations are on board. In 2015, New York hunters found themselves in a curious alliance with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Along with Audubon and many others, they defeated a measure that would have legalized TNR in New York. Rather than an isolated concern for the cats, PETA touted an encompassing empathy.

“I don’t know what it will take,” said Teresa Chagrin, an animal care and control specialist for PETA. “With so many people, there’s a disconnect between the cats’ welfare and what they kill. People have to understand that cats are non-native predators, ones indigenous animals aren’t equipped to deal with. This compromises native predators, as there’s less prey, and the cats themselves can’t handle harsh weather without significant support.”

Some cat advocacy groups, and even some in the scientific community, take issue with the math and methods of many of the studies used to shine a light on cat predation. “They made a common error,” said Dr. Lynn, referring to the Smithsonian study. “They generalized island-specific studies to mainland environments. If that range’s top end was true, cats would kill three-quarters of America’s birdlife annually. That’s why anti-cat rhetoric has reached ‘zombie apocalypse’ heights.”

But Dr. Amanda Rodewald, a Cornell ornithologist, countered this: “They did include islands, but these were Britain and New Zealand. A study similar to the Smithsonian’s by Peter Blancher has cats killing two to seven percent of Canada’s birds annually, with American studies showing at least that. That would certainly affect recruitment [the number of young needed to replace losses].”

Ted Williams, a Cape Cod-based writer and outdoorsman, is as taken by Blackburnian warblers as by woodcocks, making him as much a Thoreau as a Hemingway. Recognizing the damage feral cats do, he’s waded into the debate, urging concerted, government-sponsored kill programs.

“TNR doesn’t work, and it’s cruel to cats,” said Williams. “I call it ‘Trap, Neuter, Re-Abandon.’ You have to trap a high percentage just to neutralize colony growth. Some efforts succeed, but they take enormous resources in terms of volunteer hours, vet support, food, and trap maintenance. Meanwhile, released cats continue killing while only living because of feeding stations. Cats breed as early as six months and produce up to three litters a year, so if TNR isn’t sustained at a high level, then it’s a bust. There’s no reasoning with the Cat Mafia, though.”

Becky Robinson might be that mafia’s don, though in truth, she’s simply someone who has laid herself out caring for cats. A Kansan moved to Washington, D.C., Robinson is the founder of Alley Cat Allies (ACA), the nation’s most prominent cat advocacy group. Whatever its detractors think, ACA is a remarkable, from-nothing success story.

“We started from my Tercel,” she said, describing the D.C. neighborhood where she blundered into an alley cat colony and acted. “In short order, we were going door-to-door, finding who owned what cat while caring for the unowned ones, modeling the TNR success they’d had in Britain. Vets were hard to convince, but many facilities now are exclusively fast-track neuter-and-spay.”

TNR has flourished. Despite the legislative setback in New York, the practice has been legalized in more than 500 American municipalities and was recently sanctioned by the American Veterinary Medical Association, though as author Jim Sterba points out, the AVMA is comprised primarily of pet vets, most of whom, he said, “don’t know a thing about wildlife.”

Williams is on the side that wants the government – not citizens, whose methods to him are scattershot, vicious, and ineffective – to run euthanasia programs. (PETA’s Teresa Chagrin seconded this point about cruelty. “We’ve seen it all,” she said regarding public cruelty to cats). Robinson’s tribe thinks TNR alone can work. Both approaches are great in theory, but reality is hard on theory. Each method has limitations, and each can work only by expending considerable resources over many years.

For example, TNR’s successes – defined by colony elimination – have been observed almost exclusively in cities or on college campuses where volunteers are many and habitat is limited. Stacy LeBaron, who ran a successful campaign in Newburyport, Massachusetts, cited only one stalwart rural effort, in Nebraska.

While she says that TNR “can be successful anywhere as long as the group manages its tenets thoroughly,” in practice this has only been modestly achieved in urban settings. Rural townships have fewer financial resources and people to volunteer and perhaps place a greater emphasis on practicality than on the animal welfare notions popular in metropolitan areas.

Similarly, feral cat culling may not work everywhere. We can look to Australia, where poison and trap-kill projects are ongoing, for a model of what an aggressive cull program looks like. Dr. John Woinarski, a biologist there, noted undisputed successes on islands, but cautioned against optimism in mainland environments.

“We’ve had eradication success on offshore islands, and mainland enclosures have been remarkably successful, but these latter aren’t feasible for the high fencing costs of even small areas,” he said. “Air-dropping poisoned baits reduced feral populations by 30 to 80 percent per year on the mainland but must be sustained over years.”

In addition, Australia largely poisons only where few if any people live in an effort to avoid killing owned cats. That would be tough to do in America, especially in the heavily populated areas of the Northeast.

Splitting the Difference

When the debate comes down to data, TNR advocates are mostly on the defensive, their main strategy being to question the sky-high wildlife mortality numbers of certain studies. If wildlife managers were flippant, they’d say the only data that cat-lovers have is YouTube. Emotion counts, though, and calling for government culls isn’t the best ballot-box approach in a country paralleling the Pharaohs in cat worship.

To minimize the carnage cats cause then, colony-to-colony assessment emphasizing tailored approaches might be the way forward.

E. J. Barnes recommends just that, putting her in rare company. If Robert Frost lived today, he might have written, “Three roads diverged in a wood, and I – / I took the one never traveled by. / The one in the middle.” Having witnessed contentious TNR-euthanasia debates around Greenfield, Massachusetts, Barnes urged a mixed approach.

“TNR is more workable in cities. Wildlife isn’t nearly as diverse, and colonies are concentrated. There’s also more shelter and feeding opportunities for released cats, and fewer predators. Out in the country, there are more dispersed populations and more predators. Returning cats to that environment isn’t humane, especially up here with the winters. They have access to a broader, more sensitive prey spectrum, too, and providing feeding stations slights native predators, who scrape by while we subsidize cats.”

Blending strategies – and science and emotion – will require that each side accept frustration based on an individual’s sense of what different animals are owed. Both sides want feral cat populations sharply reduced. If TNR is accepted in urban and suburban environments but other methods are approved elsewhere, efforts could be funded and coordinated better and wouldn’t necessarily entail killing. Building on Australia’s enclosure successes, fencing unadoptable cats in rather than out might be worth a look. Not what either side wants, but détente has its blisters.

As with all issues, this one has a silent majority. Vermonter Mollie Matteson, a biodiversity biologist, understands threats to native wildlife while owning and adoring cats herself.

“For lots of people, cats are their sole window into nature,” she said. “That can be criticized, but it can also be built upon. There’s growing awareness that all creatures have a similar intelligence and emotional life to the ones we’ve chosen for pets, and as more people understand that the animals cats kill are worth protecting while straight wildlife advocates come to accept people’s love of cats as worth honoring, there’s material there for a bridge.”

Maybe, maybe not, but just attempting it beats the status quo.

Discussion *