If we treated municipal waste like the forest products industry treats wood waste, we could probably eliminate landfills – everything would be sold, turned into energy, or reused.

Ok, maybe that’s not a perfect comparison. After all, municipal waste is made up of countless materials, many of them bonded together, while the forest products industry’s waste is, in a word, wood.

Still, it’s not too much of a stretch to say that the industry is one of the most efficient around. Like the farmer who uses all parts of the pig except the squeal, modern mills, turneries, and furniture manufacturers find markets for nearly all of their waste. In fact, they don’t even like to call it that. The preferred term is byproducts.

“The only waste is the noise,” said Clifford Allard, the owner of Allard’s Lumber in Brattleboro, Vermont.

“There’s nothing left when we’re done,” said Joe Robertie, the co-owner of Precision Lumber Co., a pine mill in Wentworth, New Hampshire.

It wasn’t always that way. Not too long ago, mills used teepee burners – primitive conical contraptions – to burn mill waste, including slabs, just to get rid of it, creating huge amounts of smoke and ash in the process. Those that didn’t burn the waste stockpiled it. As late as the 1970s, many mills had mountains of decomposing bark and sawdust looming over their yards.

When Robertie got out of college in the 1970s, he went to work for Andover Wood Products in Maine. “There was a mountain of bark up there, hundreds of truckloads,” he remembers. They were dumbfounded when a guy offered 50 cents a yard and bought the entire thing. He even brought his own equipment to load it. They thought he was crazy.

Now there is not only a market for virtually every byproduct, there are competing markets for some. What happened? “Capitalism,” said Jason Brochu, the co-owner of Pleasant River Lumber Co., which operates two large pine mills and two large spruce mills in Maine.

Existing industries found uses for some types of waste and new industries developed around others. In addition, sawmills have reduced the amount of waste they create by using technology to optimize saw cuts and shifting to thin-kerf saw blades.

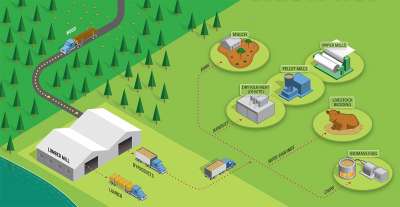

Sawdust served as cattle and horse bedding. Later, it became a primary ingredient in particle board. Then it was used as pulp. Then wood pellets. Then as fuel for biomass electricity plants. Chips were turned into pulp, then fuel. Planer shavings are bagged and sold for pet or horse bedding. Edging slabs are chipped for biomass fuel or sold in bulk to sugarmakers as evaporator fuel. Hardwood chips can be processed for playground mulch so little knees don’t get skinned up. Some turneries sell their waste blocks by the bag as wood stove fuel, while some sawmills have found higher-end markets for small offcuts. Bark frequently goes into landscape mulch – a market worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year in the United States today.

Some byproducts are still burned, but no longer aimlessly. What isn’t sold for some other use is generally burned to heat a mill’s drying kiln or to generate electricity.

Lloyd Irland, a forest economist and president of The Irland Group, a Wayne, Maine-based consulting firm, says that even the term byproducts doesn’t capture the holistic approach that’s needed in today’s forest products industry. He views leftover wood materials as joint products. “When you manufacture a two-by-four, you manufacture all this other stuff with it. And you have to market those joint products effectively because they are built into the price of your raw material. The price you pay for delivered logs includes an assumption that there’s a certain value there. And if you can’t get it out, your competitor will.”

Irland notes that sawmills didn’t lead the way in developing alternative uses for wood waste. “The market development has been pretty passive from the standpoint of the sawmills and the people who produce all that fiber,” said Irland. “Other people have done it and come to them.”

While in many cases it was entrepreneurs who took note of all the wood that was going to waste and created markets for this material, credit also goes to those in the industry who have changed with the times. At Pleasant River Lumber, byproducts (or joint products) now account for about a quarter of revenues, said Jason Brochu. “We treat it as kind of a separate business and have one person responsible for managing it companywide.”

Brochu acknowledges that the markets for byproducts developed around the availability of materials. But he adds that “the forest products industry has capitalized on that as well as anybody. There’s no waste.” Pleasant River burns some of its bark and sawdust in biomass boilers. Most of that is used to heat dry kilns, though the company has one mill with a small turbine to generate electricity. Most of the residuals are sold. “There’s nothing we don’t have markets for. We sell everything,” he said.

At Precision Lumber in New Hampshire, shavings are sold for animal bedding, bark for mulch, chips to paper mills and power plants. The company sells a little sawdust to farmers, but most of it gets burned to power its drying kiln and the rest goes to pellet mills, said Robertie. “It’s 100 percent used,” he said. Robertie estimates that byproducts account for 16 percent of Precision Lumber’s revenues, and that doesn’t take into account the money saved by burning wood waste for heat. “We burn zero oil for heating the buildings and producing steam for the dry kilns now,” he said.

The increased efficiency and new revenue streams have been especially important for mills at a time when profit margins are tight.

“They’re trying to use [the wood] in whatever way they can. It’s tough to be a mill today without doing that, whether it’s using some of that byproduct itself for energy or finding a new market for it. And biomass is probably the biggest one,” said Kathleen Wanner, the executive director of the Vermont Woodland Owners Association.

Randy Cousineau owns Cousineau Wood Products, which has a sawmill in Maine, and Cousineau Forest Products, a byproducts processing and brokering company in New Hampshire. He brokers his own mill residues and those from about 25 other mills in Maine and New Hampshire, handling about 600,000 cubic yards, or 6,000 semi truckloads, a year.

Some byproducts can be sold as is, he said. Others have to be processed. Cousineau’s North Anson, Maine, sawmill uses about 30,000 board feet of high-grade hardwood a week for the production of gunstocks, baseball bats, and drum sticks. The company also makes dyed Spectra-ply plywood for gunstocks. Offcuts from both those operations are recut and sold to companies that supply the hobby woodturning industry with blanks for bottle stoppers and custom-turned pens.

The company has mobile grinders that go from job site to job site grinding up wood waste or Christmas trees to be sold to biomass plants.

Cousineau said that for his operations, byproducts are not just icing on the revenue cake, but an essential ingredient in the mix. “We wouldn’t be able to survive” without sales of byproducts, he said. “We have to generate that revenue.”

The byproducts market, like the forest products industry overall, is in a constant state of flux as internal and external factors change.

The market for sawdust is a good example. Its use as farm animal bedding has dwindled as the number of farms has dropped and competition has arisen from other bedding products. Pleasant River Lumber still sells to the bedding market, said Brochu, but that market has shrunk. These days, a semi-truckload of sawdust can fetch a decent price, but that price depends on the location of the mill and the number of potential customers in the area.

Sometimes changes in demand, and resulting shifts in prices, can occur quickly, leaving mill owners scrambling to find alternative markets or factor lower prices for byproducts into their business plans. The announcement last fall of more paper mill closures and machine shutdowns in Maine caused prices for many byproducts to drop “dramatically,” Brochu said in November 2015. Then things got worse. In early January 2016, Brochu reported that “the overall residual markets have collapsed pretty hard. There is an oversupply of sawdust, chips, and biomass. We just received notice yesterday that two more biomass plants are shutting down March 1. It is definitely a supply and demand issue and demand is disappearing rapidly.”

This developing story illustrates the importance for sawmills in diversifying their customer base, since no market, whether for products or byproducts, can be taken for granted, said Irland, the forest economist. “The producer always has to be alert and not depend on a single customer.”

And, he said, mills need to keep an eye on policymakers, who can influence markets in especially dramatic ways. Connecticut’s recent decision to reduce the value of so-called renewable energy credits for certain biomass plants, for instance, had ripple effects throughout northern New England, where much of that biomass was sourced, Irland said.

Sawmill owners note that the benefits of using every scrap of fiber extend beyond their bottom lines. There are plenty of environmental pluses to this efficiency. For one, the waste isn’t taken to landfills. And while burning wood to heat a dry kiln or generate electricity creates CO2, that greenhouse gas would result even if the sawdust rotted in a corner of the mill yard. At the same time, that wood fuel has replaced fossil fuels that are pumped from the ground and transported hundreds, if not thousands, of miles.

“There is no greener industry than the lumber industry,” said Precision Lumber’s Joe Robertie.