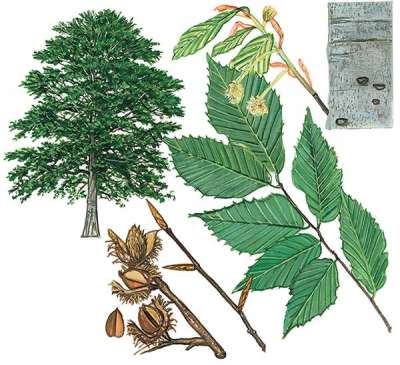

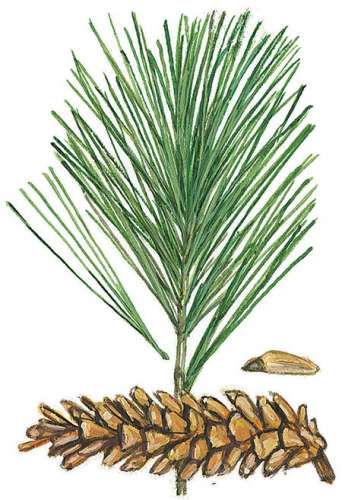

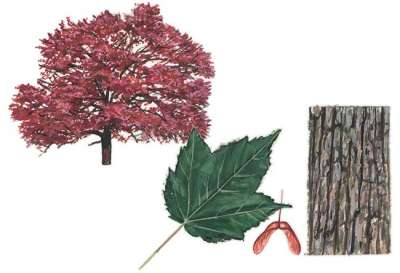

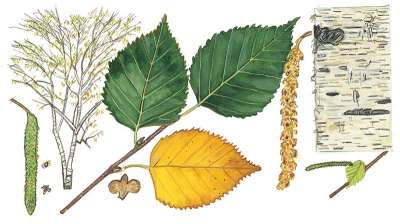

Mystery Tree 1

Can you identify these trees? Answers at the end of the article.

Illustrations by David More, from Trees of Eastern North America, by Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, and Richard Spellenberg, Princeton University Press, 2014.

“Do not be afraid to go out on a limb…that’s where the fruit is.” Anonymous

Here I am, going out on a very long limb, freely admitting that despite living among trees, earning a botany certificate from the illustrious New York Botanical Gardens – despite hundreds of miles of hiking through forests and investing in a small library of identification books, I barely know trees beyond maple, oak, beech. Or pine, spruce, and possibly cedar. Even though I can impress people by correctly naming most wildflowers on a spring hike or easily pointing out the invasive plants on the forest floor.

I admit this because I know I’m not alone. While there is a select group of people who can rapidly identify and rattle off the common – and Latin – names of trees, this ability does not apply to ordinary mortals, who recognize half a dozen species at most.

“I call all evergreens pines,” noted a gardening friend sheepishly.

“I can tell a birch from a maple or a pine, but that’s about it,” admitted another, who spends a good deal of time pursuing outdoor sports and can name the year, make and model of every car going back to well before his birth.

“It’s not so hard,” claimed my husband Ted, who takes pride in being able to pinpoint the sugar maples amid a forest of winter trees. But that’s where his knowledge ends.

And yet, even in the pages of this, my favorite magazine, writers refer casually to a tree’s species name under the mistaken assumption that readers instantly visualize the tree in question.

Why is it so hard for so many of us to tell the trees from the forest? We live with trees, especially in the Northeast. Whether sending roots under our homes or lining the roads we travel daily, trees are our most constant, visible companions in the natural world.

To help shed light on this mystery, I contacted tree experts.

“People get overwhelmed by trying to learn everything about every tree,” opined Tree Warden Gary Salmon of Shrewsbury, a Vermont forester for 36 years. (“Actually, I’d be content with identifying just the trees in our small woodlot,” I had thought. But I kept quiet.)

“I don’t think people look closely,” explained Bill Torrey, a logger for four decades in Vermont.

“We first have to learn what to look for,” said James Harding, professor of Natural Resources Management and faculty dean at Green Mountain College. “We’re not trained to pay attention to the finer details, the pointed versus the rounded lobes of different oaks, for example.”

“Some people have more aptitude than others,” according to Bill Forbes, a technical specialist with the Natural Resource Conservation Services who does wetland determinations. He added that anyone can learn over time, but acknowledged that even people in the business of trees sometimes struggle.

“It’s like learning a new language while different aspects of the language are hidden at any one time,” is how Kathy Doyle, adjunct professor of environmental studies at Green Mountain College, explained it, referring to the absence of leaves, flowers, and fruits during various seasons. It would be easier, she hypothesized, if we lived up in the trees and could see the tiny flowers and buds and leaves clearly.

And that brings up a good argument in our defense: The trees make it hard on us. They’re remote in their loftiness. They prune off their lower branches where the sun doesn’t reach, leaving us straining to see their leaves – even more so their flowers, which are generally tiny and underwhelming compared to garden blooms. When you can see the leaves clearly, there’s lots of overlap in their appearance. An egg-shaped, toothed leaf can point to basswood, elm, beech, or ironwood. Fir and hemlock needles look indistinguishable to unpracticed eyes.

Twigs are distinctive in the way they grow and divide. Too bad they, too, are often out of reach. If you can’t see the twigs, you can’t see the buds. Then there’s the fruit, which usually consists of seeds rather than something universally identifiable, like plump red cherries. The clusters of floating samaras descending from maples are easy, as are the cones of “pine” trees, but others are small and dark, blending easily into the late-autumn soil.

“Bark,” they say. The bark is always there, at eye level, and it’s distinctive in color, pattern and texture, being smooth or furrowed, scaly or firm. Except bark, the trees’ skin, is much like our own skin; it changes drastically with age, gaining lots of character. So the bark of a red oak, for example, can be characterized by cracks or ridges – two very different textures, depending on the tree’s age. Even the richness or poverty of the soil where the tree grows affects the look of the bark.

Shape could be the answer. There are the distinctively shaped “ballerina” trees with their short skirts above their graceful trunks, their upper limbs reaching skyward. Pin oaks, I learn, after repeatedly passing them on a familiar road. There’s the old oak or maple by a long-gone farm, lording over the young forest at its feet. Sure, easy. But what about all the forest trees that grow closely together? We can hardly identify the pyramidal, conical, columnar, and vase-shaped figures that define species in a pole stand.

There are the field guides, countless Internet sites, and even phone apps to help. But for some of these, you have to master obscure terminology before you can begin identification. “Pinnately compound” and “stipule” are not words in common usage.

Decoding Dendrology

The experts agree on one thing: identifying trees is hard. Hard enough that they, themselves, have struggled. Hard enough that, even after years of practice, they can be stymied. Trees are complex in their seemingly endless variety, and yet it’s their variety that makes them fascinating. A tree farm that mirrors the same tree thousands of times hardly merits a second look. Forests, on the other hand, demand many close looks.

“It helps to have keen powers of observation,” said Kathy Doyle, who finds that artistic students generally learn trees better than others. “Spending your working life among trees turns you into an expert,” said logger Bill Torrey, who can tell a tree by the smell of its sawdust.

Still, the experts are encouraging, helpful, and uniformly upbeat.

“Really, there are only about a dozen tree species that predominate in the forests of northern New England,” said Gary Salmon. (Some of those species illustrate this article.)

Look for the differences, not the commonalities, the experts suggest. Look at the soil and site conditions. Spend lots of time in the woods.

They all end with the same advice: it’s a skill, and as with any skill worth acquiring, the answer lies in practice, practice, and more practice.

It was at this point in my research that a fundamental question occurred to me: is it a skill worth acquiring? When humans lived by foraging and hunting, knowing trees was as imperative as recognizing a lion. There was the tree that yielded sweet fruits or nuts – if you knew when and remembered its location. There were others under which prized mushrooms grew. Just one kind would burn even when wet, while another’s leaves made a tonic when boiled in water.

Even today, there are practical reasons to know some trees. I recognize the “weed” trees that routinely spring up in our fields when they’re hardly more than infants with stems the width of a tulip’s. And also the old mulberry that yields a freezer full of berries, or the smoke tree I saw on a lawn, so beautiful that I absolutely had to have one.

But absent practical considerations, why should we care how a tree is classified? Does knowing that an oak is red or white render it more beautiful or important? Does this kind of recognition change our enjoyment of the stately oak?

Our desire to name things may be innate. Studies have shown that some brain-damaged patients are unable to order and name living things; it turns out that all have suffered damage to the same part of the brain. So scientists hypothesize that there must be a physical location where the ability to order and name the living world resides, making this drive a basic function of being human.

And there are, of course, pragmatic reasons. In many ways, recognizing trees is like recognizing people. In a large city, you can enjoy people watching. But when you recognize someone in the crowd – someone you met way back and now see again – the thrill of recognition is palpable. You feel a connection with this person that’s totally absent from your feelings toward strangers.

So it is with trees – indeed, with any living plant or animal.

Of course, identifying a person or a tree is just the start. With a friend, you know her life story, her family, her neighbors. To know a tree, you want to know its physiology and history.

Getting Up Close and Personal

Trees, too, can become cherished friends once you get to know them. Here are some suggestions from the experts on how to begin:

- One of the best pieces of advice is to start observing trees where we can see them individually. A town green or farm rather than a forest, explained Rob Bryan, a Maine forester who got his start in a UVM dendrology class. But keep in mind that a tree growing alone in the sun would look different when limited to a sliver of sky in a forest.

- When walking in the forest, get comfortable with one tree and then look for more like it. Then do the same with another tree.

- A tree’s most distinctive feature is its leaves, so start with those when they’re out. And since they’re often not visible when you’re on the ground, use binoculars.

- Collect leaves from several different trees and take a good look at them. Leaves can be simple, with a single leaf at the end of a stem, like maples, oaks, and beeches. Or they can be compound, with multiple leaflets on each stem. Ashes, locusts, and butternuts have compound leaves. Leaves also have shapes and margins, which can look smooth, like fine teeth, or jagged like a carpenter’s saw. They can also be lobed with deep notches, like oak leaves.

- The next easiest identifier is the leaf pattern. Maple, ash, dogwood, and horse chestnut have opposite leaves, which means they line up with each other on either side of a branch. All the other trees in northern New England have alternate leaves that don’t line up with each other.

- Buds are visible in winter, when leaves are not, and buds, too, are distinctive. You can’t confuse the single, large, pointy buds of beech with the multiple little buds (with overlapping tissues) of maples. Location of the bud is also key. Maples, ashes, and hickories have a bud at the end of the twig, while the buds of other trees, such as elm, are below the end.

- Bark is always visible at eye level, yet it may be the most difficult identifier. Not only does it look different on young and old trees, but it varies even along the same trunk. Where a tree grows also affects the bark. A tree will grow faster in a roomy, sunny location than in a dark forest; this darkness can create deeper fissures in the bark at a smaller diameter.

- Take a look at where the tree is growing. The north sides of mountains may be populated by evergreens such as spruce, whose branches angle downward when snow lands on them, allowing the snow to slide off. The south side will usually have deciduous or hardwood species such as beeches, oaks, and maples that replace their leaves each year.

- Wet and dry soil also appeals to different trees. Our common northern hardwoods typically grow in well-drained, upland soils. Very dry or shallow soils will host juniper, white pine, red pine, and pitch pine. Wet soils will grow willow, alder, ash, elm, red maple, and tamarack. In urban areas you will see box elder (a type of maple), tree of heaven, and the invasive Norway maple. At high elevations, red spruce, balsam fir, and some stunted birches will predominate. Then there are some trees that are opportunistic and grow just about anywhere, such as some poplars, red maple, grey birch, and balsam fir.

- Here’s something I’ve seen my artist daughter do: stop to draw a flower, leaf, branch, or piece of bark. “Why not just take a photo?” I asked. “It’s different,” she responded, and when I tried it myself – despite the fact that I’m no artist – I saw what she meant. Snapping a photo takes a fraction of a second, but drawing forces intense observation. If you draw a pinnate leaf, you’ll remember its shape forever.

Don’t get overwhelmed. Remember, there really are only some dozen common species in our region’s forests. If you start with those and start now, when the branching and shape are easy to see, you’ll have mastered a few species by the time the leaves unfurl, which will make it that much easier to master a few more. Visit your trees regularly so they become familiar through the seasons, and you will learn their individual personalities. While sharpening your powers of observation, the forest will yield its other charms to your newly opened eyes.

Resources

There are dozens of guidebooks, websites, and apps. Here are just a few that several of the experts recommend and that I found helpful. They are comprehensive and easy to use because jargon is kept to a minimum.

Books

Brockman, C. F., and Marrilees, R. Trees of North America: A Guide to Tree Identification, Revised and Updated. Golden Guides from St. Martin’s Press, 2001.

Maine Forest Service. Forest Trees of Maine. (Fourteenth Edition).

Nelson, G., Earle, C.J., and Spellenberg, R. Trees of Eastern North America, Princeton University Press, 2014.

Petrides, G., and Wehr, J. Eastern Trees. Peterson Field Guides, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998.

Williams, M. D. Identifying Trees of the East: An All-Season Guide to Eastern North America, Second Edition, Stackpole Books, 2017.

Wojtech, M., and Wessels, T. Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast. The University Press of New England, 2011.

Websites

“Go Botany,” sponsored by the New England Wildlife Society, is the easiest and most accurate site I’ve found. It asks a few simple questions before it provides the identification, with additional questions if needed.

Apps

Virginia Tech Tree ID or “Woody Plants of Where You Are Standing.” Once your location is entered, you can zero in on the identification by answering a series of simple questions such as leaf shape, leaf arrangement, flower color, or fruit type.

LeafSnap asks you to place a leaf on a sheet of white paper, snap a photo, and within seconds you get the answer. Easy but not always accurate.

Mystery Tree Answers: 1. Eastern hemlock 2. American beech 3. Eastern white pine 4. Red maple 5. Northern red oak 6. Yellow birch 7. Sugar maple 8. White ash 9. Paper birch