We’re doing a big story on white pine blister rust in the Autumn issue, and in tracking down art for the piece came across a cool old type-written report on eastern white pine that was published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston in September 1950. It’s a hybrid piece of writing – part historical treatise, part financial overview, part public service announcement on the need for good forestry. It’s also just fun to read because it’s old. I love how earnest things were back then. The title of the report is Eastern White Pine: Nature’s Gift to New England. One of my favorite lines in it is: “It was a good tree in the old days, and it is a good tree now.”

In reading I was struck by, as the old cliché goes, how things both change and manage to stay the same. The change is certainly there. Back then forest industry accounted for 10 percent of New England’s manufacturing jobs and forest products accounted for 30 percent of the rail freight tonnage on New England railroads. People were cutting an average of 622 million feet a year of white pine for lumber – that doesn’t count pulp or cooperage or other purposes. Between 15 and 20 percent of the pine lumber was going into box-making, which by itself was contributing around $11 million to the New England economy (about $109 million in today’s dollars).

When’s the last time you bought a locally made wooden box?

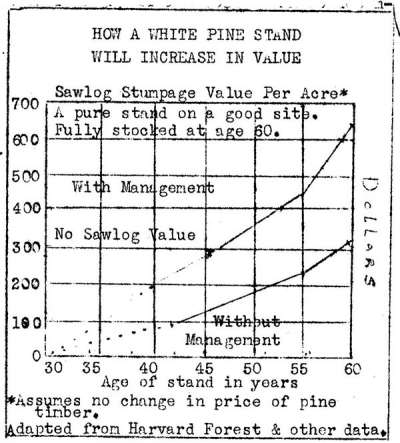

Where forestry was concerned, according to this report, the annual cut was exceeding the growth rate, and the bank was preparing for a “gap in the schedule” when there weren’t enough mature pines to cut. There was a condemnation of clearcutting practices, which had proliferated around that time. To reverse the decline, the author suggested better protection against fire, insect, and disease damage, reduction of waste, improved cutting practices, and better scientific management. He or she (but probably he, based on the fact that it was 1950) also dreamed of a future where there were better low-value wood markets that could help fund timber stand improvement work, and property tax reform that made it affordable to grow wood.

So yes, things are much different today. With the exception of a few outliers, there’s a lot less wood manufacturing going on in New England. In most places, the growth rate in the forest exceeds the harvest rate. Forest fires are practically non-existent. Waste has been drastically reduced in manufacturing and in logging operations (in this later case, perhaps to the detriment of the forest). And every state in New England has some sort of current use program that at least attempts to address the property tax issue.

At the same time, we could excerpt sections of the report and run them verbatim today. We’re still paranoid about invasive bugs – in fact, this worry has probably grown worse. We’re still raising our tiny fists against high-grading. (“Too much cutting is still being done without regard to future production.”) We’re still telling all who will listen about the importance of low-grade wood markets and property tax relief. And in some places, interested parties are still predicting an upcoming gap in the schedule, though this time it’s probably less about cutting too much pine and more about forest succession.

In Maine, where the white pine industry dwarfs that in other New England states, the forest just doesn’t seem to be regenerating pine effectively. According to this story by our friend Joe Rankin that ran in the Forests for Maine’s Future e-zine, “In 1971, Maine’s pine forest was classified as 49 percent sawtimber, 24 percent poletimber, and 27 percent seedling/sapling. Fast forward to 2012 and compare at 87 percent sawtimber, 12 percent poletimber and a measly 1 percent seedling/saplings.”

If those stats are accurate, that’s a worrisome age structure.

There are certainly a lot of readers out there who will have more insight and firsthand knowledge on this subject than I do. By all means share your thoughts.

Discussion *