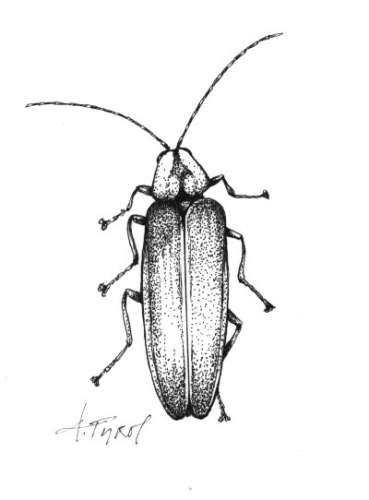

Deep down, most of us know that fireflies have a life, but a good firefly night brings such a flood of amazement and gratitude that questions about their larval phase, their diet, and their day jobs get crowded out. And what are they doing out there? Nearly all the flashes you see are emitted by males searching for females. The females have climbed blades of grass to join us in watching the luminous display.

In 1911, Frank McDermott, an amateur entomologist, discovered that more than one species of firefly was flashing in the meadow he was watching and that each had its own distinct flashing pattern, which he recorded. Jim Lloyd, who is carrying on the work of matching flash pattern to flasher, estimates that he has spent the equivalent of six years at night in the field tracking down little lights and catching and identifying the signalers – nowadays, needless to say, with more and more equipment.

However, according to Lloyd, anyone with a small, cheap penlight who knows the correct female response to a male firefly’s flash pattern can step into a field of fireflies and soon have a male eagerly exploring the penlight with its antennae.

All 22 or so New England species are kept from breeding with different species by habitat, the time of day when they are active, flash color, and, most importantly, by flash pattern. It’s a nifty little arrangement, which can be studied just by watching. The love lives of most insects are conducted by pheromones – airborne chemical signals that draw males and females together – that remain unseen by us.

Precision on the penlight switch is important. The duration, color, and brightness of a flash response, and the time delay following the male’s signal all are critical. You may need some practice with your penlight. It should be faced right into the ground; otherwise it is too bright.

But don’t distract any one firefly for too long because their time is precious. The adults typically live for less than a week and search for mates for a limited period in the evening. Some begin flashing at dusk and have extinguished their lanterns soon after dark. Others get going only when it is quite dark, and these late risers may continue well into the night. When cruising, males are exposed to predators, so attempts to mate with the wrong species could cost more than a few wasted minutes. Except for some special cases, which we will get to in a minute, the female responds only to a male of her own species.

Take Photinus marginellus, the northern twilight firefly, for example. Common over lawns and the forest floor, the male flies about four feet above the ground and flashes a single yellow light, ¼-second long, every three seconds. The female flashes back from her perch on a blade of grass. The male may dim his light as he approaches, so as not to attract other males to his find. Mating occurs within a minute or so.

Pyractomena angulata (like most fireflies, it has no common name), on the other hand, frequents bushes and trees near marshes and its eight amber flashes take place in about ¾ second, and are repeated every three seconds. The female responds ½ second later with a single flash. (These times are correct when the temperature is at about 70 degrees F. Flashing speeds up at higher temperatures.)

Too magical to be true? Well, yes. In fact, it gets downright gruesome. In the middle of this happy scene, you may find a firefly in the genus Photuris – perhaps Photuris pennsylvanicus, a common species (perhaps a group of species) in New England. Females in this genus have cracked the code of several Photinus species. With perfect timing, they flash an imitation of a Photinus female and lure in the eager Photinus male. The larger, longer legged, and more agile Photuris female then eats the unsuspecting suitor.

Imagine the effect this might have on the behavior of the firefly species that are being eaten. It’s hard times for the prey species, but a boon to biologists who study how the behavior of one species affects another. Have “dark fireflies” – daytime flying species that have lost the ability to flash and have gone back to using pheromones to find a mate – evolved in response to Photuris’ deadly appetite? Have the Photinus females, who give two short flashes instead of one in response to a male’s advertisement, found a way to keep their mates from the deadly lure of the Photuris femme fatales?

To bone up on your firefly flash patterns, visit the Montshire Museum in Norwich, Vermont, where an exhibit on local fireflies opens June 8. Jim Lloyd himself will give a talk on July 1 from 7 to 9 pm – on what might just be a good firefly night.

Discussion *