Every spring, raptors migrate by the hundreds of thousands from Central and South America to their northern nesting grounds, and every autumn they migrate back again, along with their newly fledged young. It’s been called the “greatest show above earth” and, although hawk watches throughout the Northeast regularly record upward of 15 different raptor species, the broad-winged hawk is arguably the star of the autumn show.

In any given fall, 9,000 or more broad-wings will stream past the Pack Monadnock Raptor Observatory in Peterborough, New Hampshire, some 80 percent of all individual birds tallied at that site. The majority will move through during a 10-day span in mid- to late September, soaring on thermals in groups called “kettles,” named for their resemblance to steam rising from a kettle or soup swirling in a pot.

By the time the migration wave reaches Veracruz, Mexico – swelled by the addition of broad-wings from throughout their breeding range and concentrated by a geographic bottleneck between the Sierra Madre mountains and the Gulf of Mexico – daily counts can top 200,000 birds, with more hawks whirling in a single kettle on a warm October afternoon than across the entirety of the New Hampshire migration season.

Despite a longstanding scientific tradition of counting migrating hawks from ridgetops and coastlines throughout eastern North America, much remains unknown about broad-winged migration and overwintering ecology. Where, exactly, do they spend the winter? Are there differences in migration routes and overwintering sites between birds who nest in Canada and birds who nest in southern New England, or between juveniles and adults? Which migration-corridor and non-breeding habitat is most important to their long-term survival?

With the help of satellite and GPS transmitters, researchers from Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania are beginning to unravel these mysteries.

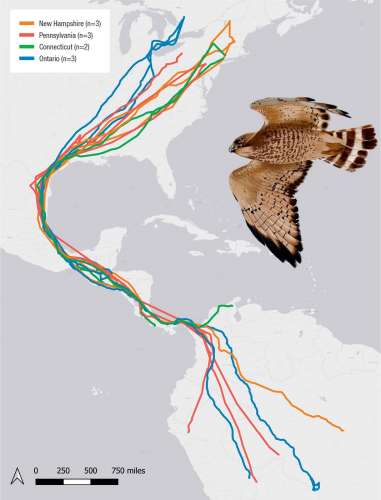

Since 2014, Hawk Mountain biologists Laurie Goodrich and Rebecca McCabe have affixed transmitters to 37 broad-winged hawks, starting with birds nesting in Pennsylvania and eventually expanding into New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Ontario, and Québec. Thirty-one of those transmitters have yielded at least one season of data, shedding light on migration patterns, premigration movements, home ranges, habitat needs, and more.

Trapping and tagging broad-wings is no easy feat. To do it, Goodrich and McCabe set up an array of delicate vertical nets – called “mist nets” for their near-invisibility – with a mechanical great horned owl and accompanying audio positioned in the center as a lure. Most broad-wings are trapped near their nests, where doting parents are more likely to respond to the owl’s perceived threat to their young. The biologists watch from a nearby blind, maneuvering the owl via remote control and hurrying out to remove any hawks from the nets shortly after they fly in. Still, it’s no sure thing.

“Thirty percent of the time,” says Goodrich, “we catch the bird.” If the hawks don’t take the bait, there’s nothing left to do but try again another day – or at another nest.

Goodrich and McCabe are based in Pennsylvania, so they rely on local partners such as the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire – where I work – and the Vermont Institute of Natural Science in Quechee, Vermont, to locate and monitor nests at other sites in advance of tagging expeditions.

Broad-wings may be conspicuous during their fall migration, but they’re quite secretive during the breeding season, so nest searches are something akin to a treasure hunt without a map, requiring long days in the field and more than a little luck. Phil Brown, the Harris Center’s bird conservation director, has monitored 21 nests over the course of three seasons for this project, discovering one when a hawk darted above his car and directly to a well-built stick nest, and another after protective parents began dive-bombing hikers on a local trail. Some nests never revealed themselves, despite hours of active searching.

“Part detective and part spy,” says Brown, “I woke early and spent long mornings in the woods following a series of clues. During those weeks, I investigated dozens of old nests and chased down scores of songbird warning calls, constantly refining my search area based on the evidence presented.”

For the most part, only adult female hawks are tagged, as the transmitters are too large for juveniles and smaller adult males. Recognizing the rarity of having a hawk in the hand, the researchers take the opportunity to collect as much additional data as possible, including the bird’s weight, wing length, bill length, tail length, eye color, and wing and tail molt. Each bird is also outfitted with a metal USGS leg band containing a unique number, and color bands for identifying individual hawks from afar through binoculars or spotting scopes.

Finally, each hawk is given a name so that students, birders, and others can more easily follow along from home via the migration maps and stories on the Broad-winged Hawk Project website and Facebook page.

“Nubanusit” means “wing-shaped” in Abenaki and is the largest lake in the Monadnock Region of southwestern New Hampshire, a few miles as the hawk flies from where that bird was tagged. “CU Home,” the first broad-wing to be tagged in the state of Connecticut, comprises the initials of the three founders of the Northeast Hawk Watch.

Transmitters typically last one to two years before their batteries wear out, and it’s common for tagged birds to go silent in the winter months, when poor cell service and dense canopy cover in the Neotropics limit data transfer and block the solar panels that power the batteries. Most of the data upload the following spring, when the hawks begin their journeys north under open skies. Some birds, however, disappear forever. “Elizabeth didn’t come back. Penny didn’t come back,” laments Goodrich. “We never know why.”

Migration is fraught with peril, and broad-winged wintering habitat in South America is threatened by deforestation, wildfires, and illegal mining. Population declines have also been noted in certain parts of their breeding range, particularly where forests are being lost to development. Broad-wings are now listed as a species of conservation concern in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey.

“I will be curious to see how broad-winged hawks will fare over time,” says McCabe. Between habitat loss and other dangers such as rodenticides, vehicle collisions, and unrestricted hunting and trapping on their wintering grounds, she wonders, “What will be left for them?”

The hope is that the data generated by this study – the only one of its kind – can be used to protect broad-wings not just on their breeding territories in the Northeast, but across their full range.

One of the most surprising findings so far is that hawks who summer within a few miles of each other might spend their winters a thousand miles apart. Some birds from Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Ontario commingle in Colombia, while others fan out to Brazil, Peru, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Venezuela, Surinam, or Costa Rica. (Whether broad-wings breeding in the Midwest and western Canada also lack this “migratory connectivity” is still unknown. In the coming years, Hawk Mountain biologists hope to tag more birds on those nesting grounds to better understand the western flyway.) This is not what the researchers expected, and while such scattered dispersal can make conservation more challenging – because there is no concentrated geographic area on which to focus stewardship efforts – it may ultimately afford the species greater flexibility to adapt to changing conditions.

While there does not seem to be a landscape-level pattern of migratory connectivity, some individual birds have shown strong fidelity to both their nesting and overwintering grounds, offering opportunities for cross-cultural collaboration on raptor research and conservation.

“Harris,” the first broad-wing to be tagged in New Hampshire and one of only a few males in the study, spent the winters of both 2021 and 2022 in a rural area between the municipalities of Sabanalarga and Buriticá in north-central Colombia. Last winter, Ana Maria Castaño Rivas, the deputy director of conservation at Conservation Park in Medellin, Colombia, and a member of Hawk Mountain’s board, reached out to her network in search of additional information about Harris’s winter habitat. Within days, she received photos and geospatial data from multiple groups, including several young raptor biologists who were surveying for eagles in the area. Their images of tropical dry forests, steep river canyons, and humid montane woodlands painted a very different picture from the mixed hardwood forests of Harris’s Granite State home – a comparison that would have been nearly impossible without the transmitter data and the enthusiasm of Rivas’s Colombian counterparts.

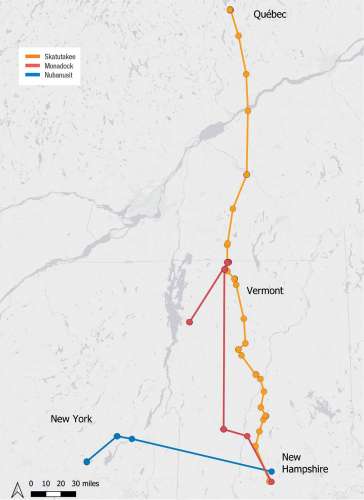

Equally revelatory is the fact that approximately 30 percent of the tagged birds undertook premigratory movements; that is, between nesting and fall migration, some birds flew west or even north, spending anywhere from one week to two months there before eventually turning back around and heading south to Central or South America. “They’re not wandering,” says McCabe. “They’re making a direct, beeline movement to a specific location, staying there, and then migrating.”

In early August 2022, a few weeks after her young fledged, “Skatutakee” – named for the small mountain within view of her nest – left her breeding territory in Dublin, New Hampshire, and flew to La Tuque, Québec, where she stayed until mid-September. Between August and November, she traveled more than 6,000 miles – 600 of which were “extra” north-south movements associated with her pre-migratory flight – and navigated her way through 13 different countries before settling in Bolivia for winter. The following spring, she returned to New Hampshire, where she experienced a nest failure in late July and promptly headed for Québec once again.

Every research project worth its salt asks at least as much as it answers, and this one is no exception. Why would a bird who is about to undertake a lengthy, energy-intensive journey choose to fly hundreds of miles out of her own way? Do males do this, too? Why do some hawks take a detour, while others fly directly south?

The tracking data also underscore the magnitude of migration in these birds’ lives. No mere commute, their journeys take 60 to 90 days each way, not including premigratory movements. In other words, some broad-wings spend roughly half the year in migration – more time than they devote to either their wintering or nesting grounds. Preserving forested habitat along their migration routes may be every bit as important as conservation efforts in their summer and winter territories.

Every line traced on the migration map deepens our collective understanding of broad-winged hawk ecology, but there is still more to learn. In the future, Goodrich and McCabe plan to tag more hawks in both Vermont and Québec, along with an enigmatic subpopulation that overwinters in Florida and whose nesting whereabouts are yet unknown. They’ve also got their sights on the western flyway and – when technology allows – males and juveniles. And they have just started tagging birds that have been rehabilitated after injury or illness, to see how these special patients fare after release.

Both researchers have been heartened by the far-reaching interest in their study, and by the many cross-continental conservation connections that have formed along the way. If they’ve learned anything from this project, says McCabe, it’s that broad-wings are “everyone’s bird.”

Discussion *