When gold was discovered in 1849 at Sutter’s Mill in California, the famous gold rush of 1849 ensued with profound consequences for the West and its native population. Sixteen years later, in East Montpelier, Vermont, C. Hinkley Stevens waded into the river behind the local post office to retrieve a large freshwater mussel that he had spied from the riverbank. It was another “Eureka!” moment. An account in the Barre Daily Times elaborated:

Mr. Stevens went back of the post office one afternoon and found an extra large clam. It measured nearly eight inches in length. On opening it he found a large pearl. It did not take long for the news to travel. In a remarkably short span of time men, boys and even women left their work to go to the Winooski river to look for clams, for clams meant pearls. Business men neglected their trade in order that they might be lucky in getting a big pearl.

While perhaps not as lucrative as striking gold, the pearls were still incredibly valuable. H. B. Ramsdell, father of the owner of the Daily Times, found a pearl that he sold for almost $1,000. (Remember, that’s in 1800s dollars.) L. Bart Cross, of the famous Cross Cracker Baking Company, owned one worth $800 that was found in the river near Middlesex, and Annette Upham of Barre had a necklace of Winooski River pearls that was valued at $5,000.

Fresh water pearl mussels, sometimes mistakenly called clams, have an interesting history. They are bivalves (Margaritifera margaritifera) that are among the longest-living of all invertebrates; many live well over 100 years. One in Estonia was reported to be 134 years old. The mussel has modest mobility, with a “foot” that permits it to travel slowly and even bury itself on the river bottom. With a hinged shell, it somewhat resembles the soft-shell steamer clams that are harvested in the mud flats of Maine. Fresh water pearl mussels may be found in Europe and eastern North America.

At birth, sometime in late summer, the larvae are ejected from the adult mussels in prodigious quantities, ranging from one to four million in a single spawn. The lucky few that are able to attach themselves to a trout or salmon fry have a chance at survival, but the rest will perish. The almost microscopic larvae resemble miniature mussels holding their shells open until they come into contact with a young trout or char, at which time the mussels clamp down upon the fish’s gills or fins and travel with it for the next several months. Late in the following spring, they drop from the host fish and begin an independent life, burrowing into the river or lake’s bottom.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, pearl booms occurred in the eastern half of the United States – from the Adirondacks in the 1890s to aptly named Muscle Shoals, Alabama, in the 1990s. While pearls were the most sought-after prize, eventually a profitable use was also found for the discarded shells – they were turned into buttons.

Manufacturers of pearl buttons, a longstanding feature of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century fashion, paid from one to two dollars for a hundred mussel shells. In 1884, a factory in Springfield, Massachusetts, paid button-makers by the piece; skilled craftspeople could make between two and three dollars per day. Eventually, mother-of-pearl buttons were replaced with plastic, and the mussel fisheries, like many a Western gold mine, once ripe with the promise of fortune, faded from memory.

But for many decades, “pearl fever” was a real phenomenon as people looked to strike it rich. Mr. Stevens sold his gem chronicled in the newspaper account for $500 – a value of more than $7,500 in today’s currency. It was a scenario that had precedent. One spring afternoon in 1857, David Howell, a Paterson, New Jersey, shoemaker who escaped tedium by fishing, gathered a “mess of mussels” from Notch Brook to fry for dinner. As he plucked the bivalves from the cooking grease, he found a large pearl weighing nearly 400 grains. George Kunz, in his 1897 treatise on freshwater pearls, noted:

It became known as “The Queen Pearl” and was sold by Tiffany and Company to the Empress Eugenie of France for $2,500. Today it is worth four times that amount. The news of this sale created such an excitement that a search for pearls was started throughout the country. The mussels at Notch Brook were gathered by the million and destroyed, often with little or no result. Howell searched for other mussels, and his example was followed by his neighbors. Within a few days a magnificent pink pearl was found by a Paterson carpenter named Jacob Quackenbush. The pearl weighed 93 grains, and was bought by Charles Tiffany for $1,500.

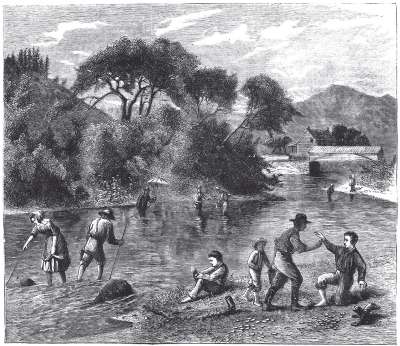

As word of the discovery spread, fortune-seekers took to rivers throughout the eastern half of the country to exploit the bounty that was teeming in their waterways. Many, like nineteenth century outdoor writer Sara Muller, waded in rubber boots in late summer or early fall, when the water was low.

“Then,” she noted, “the water is apt to be clear and the mussels can be easily seen.” She also enjoyed gliding through the shallows in a canoe and reaching over the side to pluck the bivalves from the bottom easily. While Muller took mussels from southern Vermont lakes and streams, a different method was employed in the Winooski near Montpelier. Mrs. Rowland E. Robinson, in the May 1873 issue of American Agriculturalist, described the fishery upstream from the state capital.

It seems that in this country fresh-water pearls are found most abundantly in the Winooski River in Vermont, not far from its source and in small tributaries. The clams were once found in any part of the river, but they have been hunted so much they are more usually found in deep water alone.

The instruments necessary for pearl hunting, as it is commonly called, are an iron rod, flattened at one end, with barbs cut in it to draw out the clams, a handled basket to carry them in, a stout knife to open the shells, and a box of fine cotton in which to put the pearls.

The pearl hunter was further advised to carry an umbrella to mitigate the reflection of the sun on the water’s surface. The hunter would thrust the flattened point of the iron rod into any shell spied on the bottom and, as the mussel closed its shell and fastened on the barbed point, he would pull it in and place the mollusk in the basket.

When satisfied with the number he has got, he carries them to the bank where he sits down and opens them. Often thousands of shells are opened and the inmates destroyed without obtaining a single pearl.

One usually smelled the rotting pile of mussels well before seeing the pearl fishers at their grisly work.

Robinson interviewed C. Hinkley Stevens, the East Montpelier resident whose discovery launched the pearl rush on the Winooski. Interestingly, Stevens, like his counterpart in New Jersey, listed his occupation as shoemaker. Stevens was described as “one of the most successful pearl fishers of that region and the one who some years ago found the largest pearl that has been discovered in the United States.” Stevens described how he had found that mussel “in two feet of water where it ran swift. The pearl is 5/8 of an inch in diameter, round as a ball, and of fine luster. It is now owned by a gentleman in New York City.”

In 1903, two Plainfield boys, Neal Knapp and George Henry, brought pearls they had found near their home to Barre and sold them for several dollars, according to an account in the June 6 Barre Daily Times:

The two boys have been hard at work for two weeks of pearl fishing. On Thursday they discovered a large one, as big as a pea, round and with good color. The fact that the boys have succeeded in getting a few pearls recalls the days when pearl fishing was the main object of half of the people of Plainfield as well as in Montpelier. This was just after the close of the Civil War. The older men in town have many stories to relate about the large pearls that were found then. The fishing was conducted all that summer but, as nearly all the clams, both large and small were hauled out of the river, the craze died out and regular business resumed. While it did last it seemed as if the people would go wild in their endeavors to get even a single pearl. People from all over the state came to Montpelier and East Montpelier. They came from other states and all had a desire to get rich quick.

Discussion *