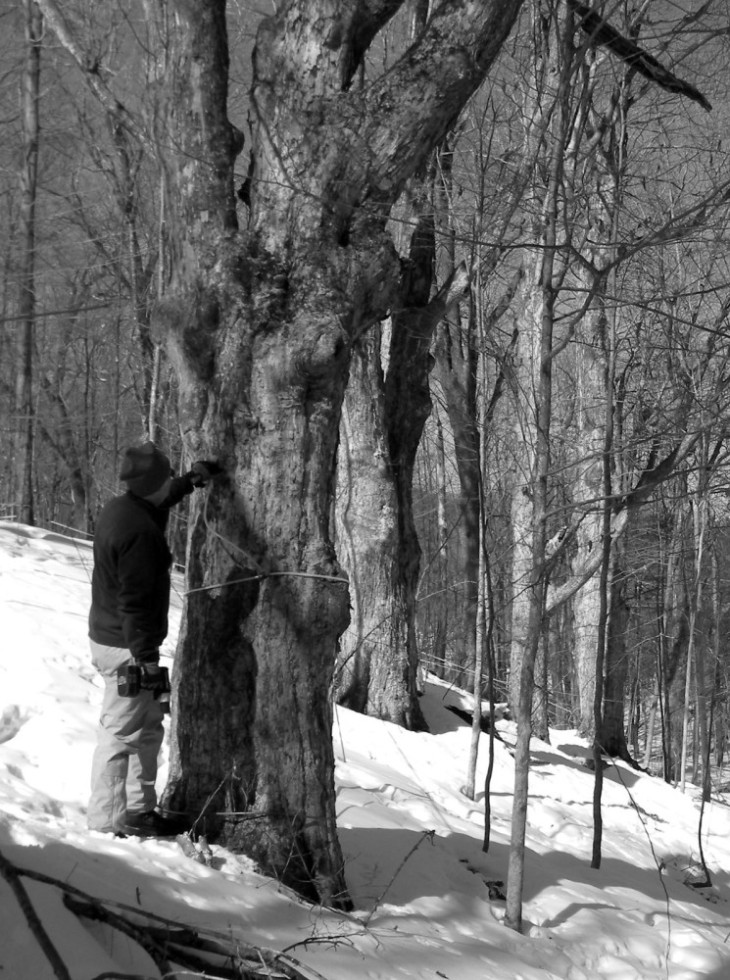

Loving the woods, loving working in the woods – it’s difficult to do either without an appreciation of history; after all, the forest we see today reflects the actions of those who have gone before us. I’ve been sugaring a piece of land in southwestern Vermont since I was tall enough to hang a bucket, and yet the sugaring history of that land goes back more than a century. Generations of sugarmakers have worked these woods. During sugaring season, there are a lot of hours in the woods, a lot of time in your head, so I’ll often think of those old ghosts, men with names like Abel Webb and Bliss Willoughby, about whom I know nothing.

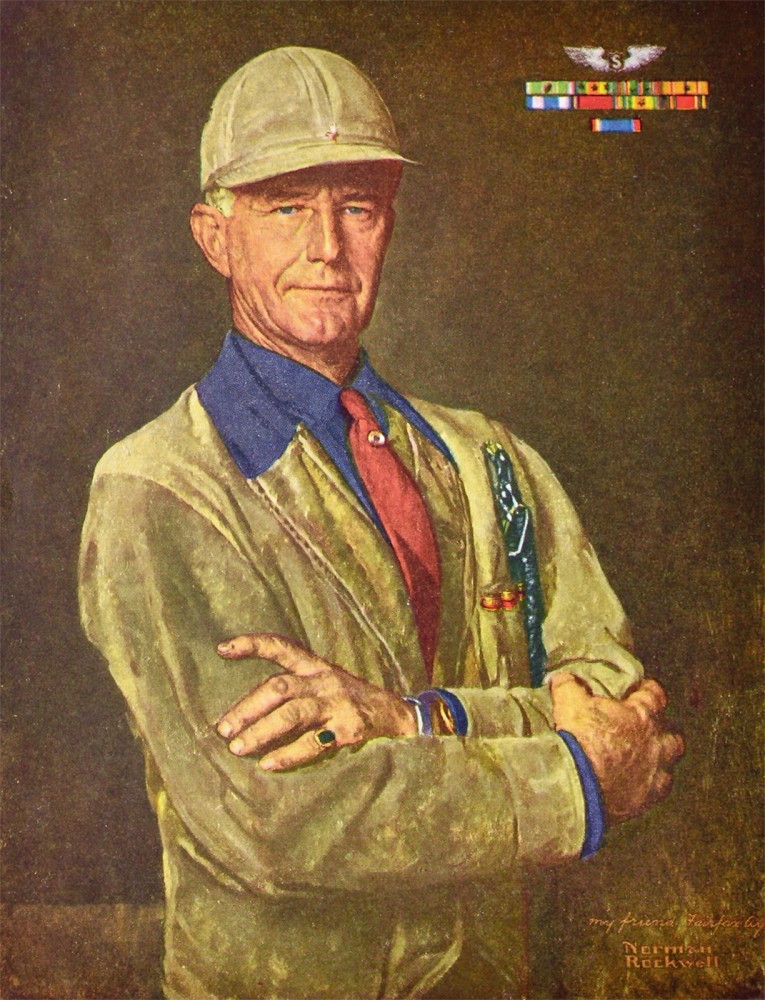

I do know something about the man who sugared these woods directly before my family, however. In fact, everyone who’s lived here for any amount of time knows something about Henry Fairfax Ayres. Over the course of his 42-year tenure in this little town, he was both exotic outsider and local color of the brightest shades – the local paper once wrote that his “life spilled out of the normal channels of description into the realm of myth.” I don’t even know how to begin stringing descriptors together to introduce him to you; I guess I’d start with warrior, inventor, environmentalist, showman, sugarmaker, and farmer, if you can picture that.

It’s logical to start with the warrior bit, as the Ayres family business was soldiering. His thrice-great grandfather, Henry Dearborn, was on George Washington’s staff and was Secretary of War under Jefferson. His paternal grandfather was Major General Romeyn B. Ayres, who led a division of the Union Army into the Battle of Gettysburg. His maternal grandfather, John Walter Fairfax, was an assistant adjutant general in the same battle, but he fought for the Confederacy. Henry’s father, Charles, fought at Wounded Knee – in fact, Henry, then just a toddler, was in the cavalry camp at the time. Charles later served as a colonel in the Spanish–American War and in the Philippines before being forced into retirement after getting into a verbal altercation with future President William H. Taft while defending his wife’s honor. She had been defending teenaged Henry’s behavior – from how I interpret reports of the event, it seems that Henry was flirting with some illicit female guests at an all-boys school.

Henry was born in 1886 near Leesburg, Virginia, in a house that was once owned by President Monroe. He was a middleweight boxing champ at the Virginia Military Institute before he transferred to West Point, where he roomed with George Patton. He fought in World War I at Saint-Mihiel and in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive – this was the largest, bloodiest American battle of that savage, bloody war. Ayres was cited for gallantry. He’d later re-enlist so he could fight in World War II – he was in his fifties then – and as a colonel in the Army Air Corps, he received three battle stars and a commendation ribbon.

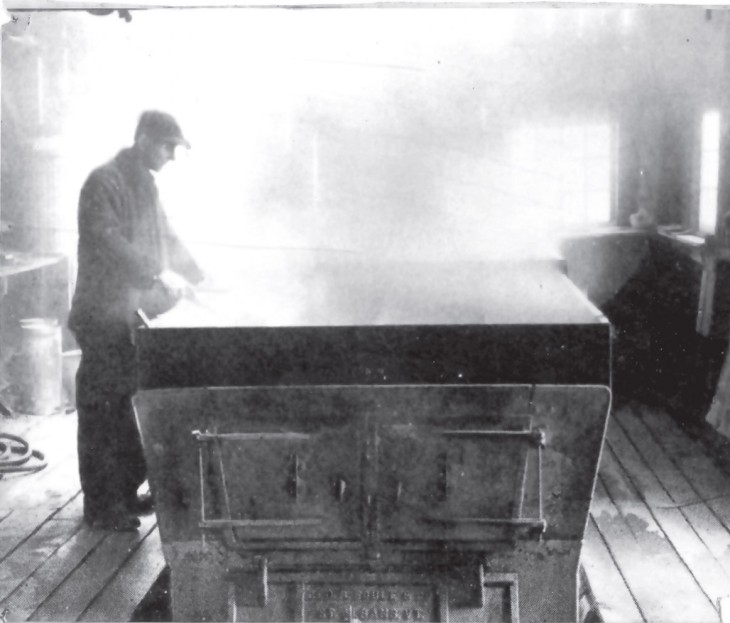

Between the two world wars, Ayres had moved to Vermont and become interested in farming and maple syrup production. You may have seen his sugarhouse and not even known it, as he befriended Norman Rockwell, who at the time lived just up the road; there’s a five-by-seven-foot photographic mural of the two of them together in front of the sugarhouse that has, at various times, hung prominently in both the Norman Rockwell Museum in Rutland and the Agency of Agriculture, Food, and Markets building in Montpelier.

Ayres knew nothing of sugaring when he moved north. Vermont Life published a feature on him in 1949, and in that story, he recalled that someone asked him shortly after he arrived if he was going to sugar in the spring. He reflexively said, “Yes.” Afterward, he felt he needed to make good on the statement, so he devoured everything he could find on the subject and invested in equipment. Within a decade, he was producing between 1,200 and 1,500 gallons of syrup a year, which would have meant he put out around 6,000 buckets.

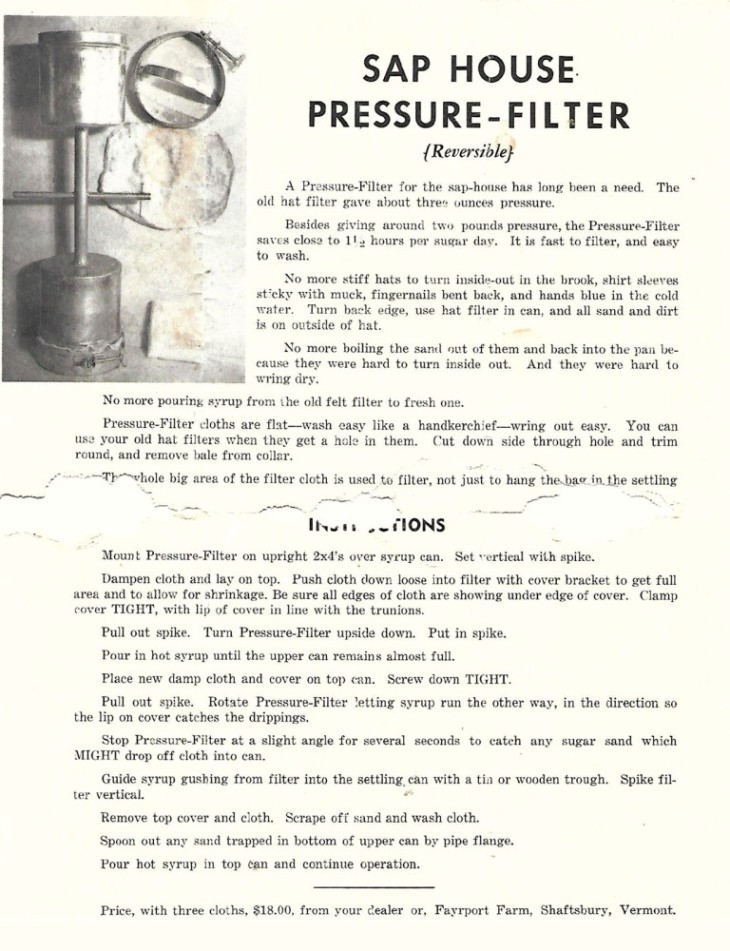

A born tinkerer, Ayres immediately went to work inventing contraptions to aid in the endeavor. He was one of the first sugarmakers in this area who used tubing. Our woods are still full of the one-inch galvanized pipe that ran with the contours along the ground; this old infrastructure covers maybe 20 acres. At the terminus of each spur line is a 90-degree header with a cap; men would collect the sap from buckets that hung from the trees, then they’d dump the sap into the tubing system where it would run (eventually) to the sugarhouse. Ayres invented an early filter press that looked sort of like a barbell – you can see an ad on page 62 that describes it. You know those Leader check-valve spouts that were “invented” a decade or so ago? Ayres filed a patent for a check-valve spout in 1955 that clearly served as the prototype.

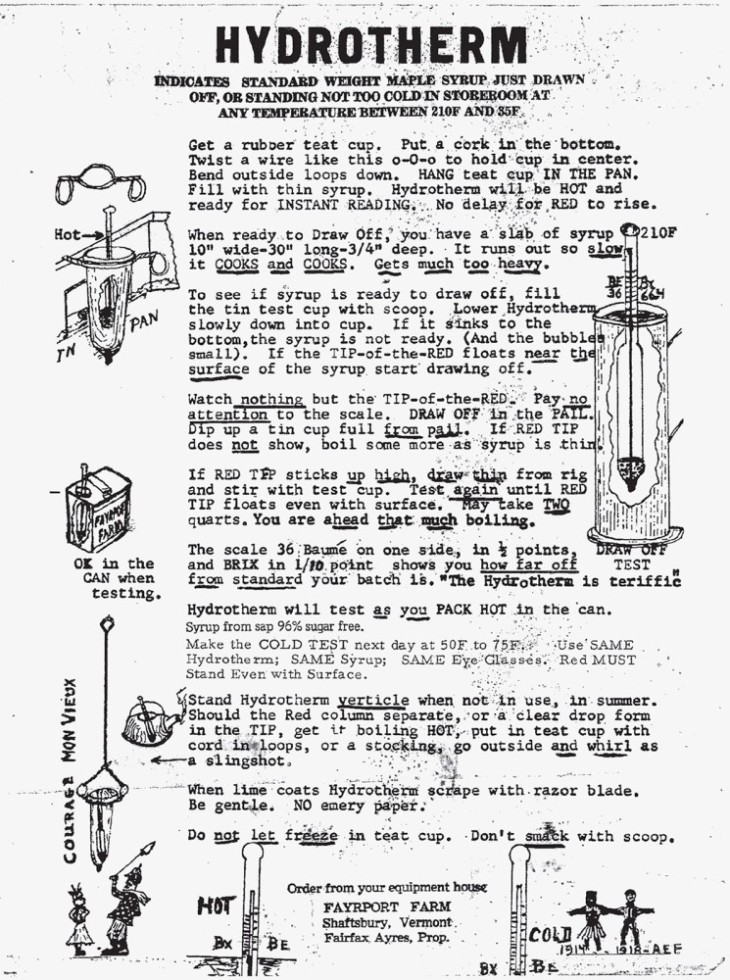

Ayres’s most famous sugaring invention remains the hydrotherm, a combination hydrometer and thermometer that sugarmakers still use today. Syrup has to be a certain density to be legal. Having the correct density is also in the producer’s best interest. Syrup that’s too thin tastes weak and is prone to mold, and syrup that’s too thick will develop rock crystals, which consumers don’t want to pay for; plus, you’re giving away product. The catch is that the density changes as the syrup cools, so to nail it, you need a thermometer, a hydrometer, and – if you don’t have a savant-level mathematical mind – a cheat sheet that gives you Baumé or Brix readings at various temperatures. The hydrotherm combined all these things into one instrument. Check out the homemade ad on the opposing page and the insight it gives us into the man. The contraption itself is ingenious – to conceive of it, you need a good grasp of the laws of specific gravity. Yet the explanation of how to use it is so downhome – I love the idea that you need a teat cup and a homemade wire shaped like o-O-o. And then there are the strange illustrations of the people – Ayres had a son but not a daughter, so I’m not sure who the child with the hands on her hips watching the sugarmaker whirl the hydrotherm is. “Courage Mon Vieux” – “courage, old friend” – is likely a World War I reference, as is 1914–1918. AEF must mean American Expeditionary Force. But how interesting that this code made its way onto an advertisement.

Ayres died at age 92 in 1979; I was four years old then, so if I met him, I don’t remember it. It’s hard to write about a man you’ve never met; it’s even harder to write about a man you’ve never met but about whom you’ve heard stories for your whole life.

Most of the stories people tell about Ayres are full of bravado. He not only roomed with General Patton but knocked him senseless in a fight. He had a bomb cellar with reinforced concrete walls and a four-inch-thick steel door, filled with munitions, live hand grenades on the mantel, a machine gun mounted in the front lawn. (The machine gun may have been the same one featured in Rockwell’s famous “Let’s give him Enough and On Time” poster.) He drove around in an old Army jeep and called men “soldier” or “sailor.” In one story, he found one of his hired men standing around by the sugarhouse and barked at him, letting him know in no uncertain terms that there was sap to be collected in Rupert – a town an hour’s drive to the north where Ayres had another sugarbush. The worker was so terrified he jumped into the Jeep, which was connected to a trailer-drawn gathering tank, and sped away, not realizing until he got to Rupert that the tank he was pulling was already full of sap.

Stories like these turn Ayres into an R. Lee Ermey-like caricature, and so we’re left trying to scavenge scraps of deeper truth from snippets of detail. He was married several times, which seems to indicate that he must have been both charming and hard to live with. His grandson remembers him as being “terrifyingly stern,” and yet the drawings on the hydrotherm ad, the hand-punched tin signs in the pet cemetery at the edge of the sugar woods memorializing black setters with names like “Mr. Gilliam of Virginia” (1952–1969), hint at a softer side. He had a rich civic life that included donating land and designing a lodge for the Masons and serving on the Vermont Roadside Council, the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association, and the County Regional Commission. Ayres was an environmentalist before that term existed, campaigning aggressively against road salt and forest grazing and billboards, which marred up the countryside. (Apparently there was a large billboard in the meadow across the road from his house; when Vermont passed legislation to make billboards illegal in 1968, within the hour, he was down there with his chainsaw taking care of the problem.) He was an early proponent of recycling programs and hated the idea of burying garbage in the local landfill; he hated, too, the interstate and other four-lane highway systems that fragmented the countryside.

Ayres was a successful inventor who sought patents for everything from skis to fertilizer to wine corks. He perfected a pressed-steel railroad brace for the Union Spring Company that went into wide circulation. Many of his patent designs were ingenious and elegant, even if they didn’t turn out to be bestsellers. And yet the inventor’s aspect of his life had a freelancing, dreamer-type quality to it. I have a file of his entitled “patents” that shows some humorous back-and-forth he had with automakers as he tried to get them to buy an idea that he refused to tell them until they’d signed on. There are letters from lawyers who had to remind him he couldn’t patent ideas. The letters show he had a restlessly creative but somewhat undisciplined mind – interesting in a man whose external life oozed order and discipline.

The phrase “Virginia colonel,” especially if you say it in a Southern accent, evokes the grand social traditions and romance of the antebellum South, and there was more than a dash of this in the Ayres persona. A young reporter from the local newspaper wrote a lyrical profile of Ayres in 1975: “A visitor to his secluded Vermont farm is offered an undiluted gulp of stories, exhortation, and advice, all delivered with appropriate gesticulations and sound effects.” Channeling the politics of the day, the reporter left readers with the impression that Ayres was straight out of a Walter Scott novel – someone who epitomized an “aristocratic, military vision of a heroic, honorable life, where servants and women knew their place, and life was oh so well ordered.” (I think there’s insight in the observation, but the parts that bite need to be considered in the context of the war between the generations that was going on in 1975.) A woman in town I know remembers, or remembers stories about, elaborate parties that Ayres and his much younger wife would throw. I can imagine earlier get-togethers with Rockwell – maybe the writer Dorothy Canfield Fisher who lived up the road, heads of industry from New York, whom he would have known from his stint as a securities broker, up for the soiree.

But in most of the correspondence I’ve read, Ayres very much identified as a Vermont farmer and sugarmaker. He signed his name, in letters to some business interests, simply “H. F. Ayres”; sometimes he used the descriptor “farmer.” He wasn’t playing at these pursuits – he was earnestly practicing them. His grandson remembers that he spent most of his time in the barn, in his workshop. That he smelled like grease and oil. He undoubtedly found the work therapeutic. In the Vermont Life story, the Colonel recalls the Second World War, telling the reporter: “There were about 80 of us officers on that convoy duty . . . at sea with the reinforcements for from 10 to 30 days, then back in a day or two, flying. Our average loss of weight, per convoy job, was nearly 11 pounds. Do you wonder Vermont, and Shaftsbury, look good to me now?”

Ayres was a keen self-promoter – his obituary in the local paper wryly noted that “A great uncle designed the Confederate flag and died from the same volley that killed Stonewall Jackson, according to obituary material which Col. Ayres left on file and periodically replenished.” And yet his public voice could be self-effacing. This seems contradictory, and would be in today’s culture, but I think it made more sense in Ayres’s time. Back then, successful men were often driven, go-getter types – they were salesmen and pitchmen and strivers who sought to make their mark, to make the papers. But this was all cut with a cultural humility that came from living through the Depression; also, from rich and poor alike serving side by side in two bloody wars. As David Brooks pointed out in his book The Road To Character, the ethos back then might be described as: nobody’s better than me, but I’m no better than anyone else; whereas today’s self-promotion can often be boiled down to: look at how special I am.

I’m finding it impossible to separate man from myth, which was clearly Ayres’s intention. I guess the question is whether there was a deeper level to him, and while I don’t know for sure, the answer in these cases is almost always yes. I think a lot of men of that generation – especially military men – hid, to a certain degree, behind a façade. Former President Dwight Eisenhower graduated from West Point seven years after Ayres; after Ike’s death, his widow, Mamie, was asked if she ever really knew her husband. “I’m not sure anyone did,” she replied. One of my favorite stories about the Colonel that shows a layered personality involves a time when Junior Harwood stopped by to take a Jeep ride to look at some timber up on the mountain – this was later in life, when the proud old pilot had become a famously atrocious driver. Junior remembers the Colonel’s shuffling down the front walkway, in his eighties, pince-nez resting over one ear, spine hunched, and sliding behind the wheel – at which point his wife comes exploding out of the house telling him he’s not to drive; the Colonel’s eyes hardening, and him barking back that he is, too, going to drive. Strong language from both of them continued as the Jeep lurched and swerved down the hill. When they got to the bottom, the Colonel looked over his shoulder to confirm he was out of sight of the house. Satisfied that he was, he stopped, set the e-brake, and said to Junior, “Soldier, you’re going to take it from here.”

One of the Colonel’s big campaigns in the 1940s, as chair of the Vermont Maple Sugar Makers’ Association, was to raise the price of syrup to a then-unheard-of seven dollars per gallon, an act that came about only after “a knock-down drag-out fight.” That it was a campaign is noteworthy. He didn’t move here, start making syrup, and then charge seven dollars a gallon for his quote-unquote superior product. He was not a lone wolf; he was a leader of men, and so he worked to push the whole industry forward. In the Vermont Life story, he’s quoted saying: “Let doubters doubt the work that goes into sugaring, from getting the wood through gathering and boiling to the final product in the can or jar. Every man who’s sugared knows it has its fun and satisfactions, but he also knows it’s work. Only the fellow who figures his time’s not worth much, come March, because there’s not much else he can do then, could agree that syrup and sugar aren’t worth present prices.”

He won this argument – a move that helped legitimize the craft and raise all ships. One of the arguments that he lost was over his idea that all the maple syrup in the state should be centrally reprocessed, standardized, and marketed under a state-quality label. If he were alive today, he would note that in the past 50 years, the US has lost 80 percent of the global market share to Canada; he’d note that as recently as 10 years ago, Vermont syrup was still getting a 10-cent-a-pound premium based on its name value – but no longer. He’d also note how the industry is consolidating and how bulk markets are becoming inaccessible to small producers. Ten years ago, I could sell bulk syrup to three packinghouses within a three-hour drive; today, two of those packing houses have locked-in supply contracts with mega-producers and don’t want my syrup. And, really, why would they? Why would they buy in dribs and drabs from 1,000 producers – cutting 1,000 checks for an inconsistent product in an inconsistent and incoherent supply chain – when instead, they can just cut one check to one mega-producer and have a clear chain of custody from forest to container? Ayres saw this coming 80 years ago. I’m not sure that his co-op model would have been better than what we have today; ask a Canadian producer how they like their socialized system, and you’ll get nuanced answers. But if you’re a small producer who’s distressed watching the bulk markets’ race to the bottom, you might decide that, much like his check- valve spout, the Colonel’s idea was a couple generations ahead of its time.