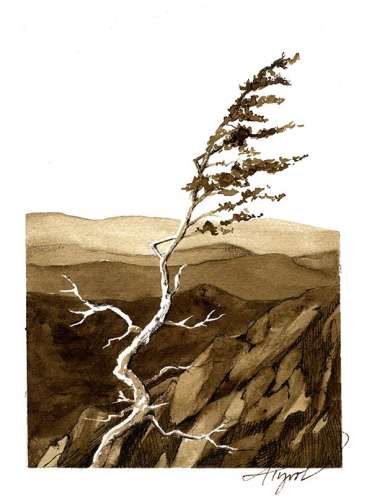

Krummholz is the original bonsai.

Stunted and gnarled, it grows in rugged environments: cliffs, mountaintops, canyon walls. Often very old, it inspires us with its tenacity in the face of harsh conditions.

The word krummholz means “crooked wood” in German. In the Northeast, when we speak of krummholz, we’re talking about the matted, dwarfed trees that circle the tops of some mountains, separating lower elevation full-size forests and true alpine areas. Balsam fir, black spruce, and heartleaf birch are the dominant species, standing no more than eight feet high. Sometimes they’re only knee high. Sometimes only ankle high.

I’ve always loved the krummholz zone, especially in a fog, when ghostly tendrils snag on the tips of the branches. It seems like a place out of time, where meeting an elf or a gnome would not be unusual. Maybe that’s why the trees that grow here are also called elfinwood.

So what accounts for these trees’ wizened appearance? Ken Kimball, Director of Research for the Appalachian Mountain Club, said that the pruning effects of fierce wind and ice buildup kill the apical buds – the growing tips – leading a tree to grow horizontally rather than vertically.

Krummholz literally lives on the edge. It grows “where a tree’s resource gains exceed its losses by the thinnest of margins necessary to sustain survival,” according to Dan Sperduto, the U.S. Forest Service botanist for the White Mountain National Forest. The factors for krummholz are complex, and can include latitude, geography, elevation, location, temperature, soil, growing season, wind, snow cover, ice, exposure, and moisture. In northern New England, the crucial ones appear to be wind and ice.

Tree line, or forest line if you want to be precise, varies widely around the globe. Kimball noted that in the Alps, forest line begins well above 6,000 feet, even though this European mountain range is more northerly in latitude than New England. In the Rockies, the tree line also starts much higher. Even within the Presidential Range of New Hampshire, the forest-alpine boundary varies significantly, from 3,400 to over 5,000 feet. Further complicating matters, krummholz is not always confined to the forest-alpine boundary. “I can show you balsam fir growing a stone’s throw from the summit of Mt. Washington,” Kimball said.

Why does our region’s krummholz appear at lower elevations?

The answer might lie in our notorious New England weather and the proximity of the ocean. The higher peaks in our region lie at the nexus of clashing weather systems – howling cold fronts out of Canada and warm, moist southern flows. When large air masses meet the mountains they are forced upward; their winds accelerate and moisture is squeezed out. This creates summit cloud caps that in winter sheathe everything in rime ice. Up there, it isn’t safe to grow tall.

Despite its size, krummholz is often very old, older than the same type of trees growing in more hospitable environments. “It depends on the species,” said Sperduto. “But balsam fir krummholz can be at least 150 years old, which is about twice the age it normally gets to. Black spruce can approach at least 200 years.”

There are prices to pay for living large, and pluses to growing slowly and keeping your head down. “It is a common theme among trees – growing tall and big and fast does not beget great age. These tactics make them vulnerable to wind and other natural forces,” Sperduto said. “More often, old trees are those that grow slowly by surviving tough environments at the extremes of their tolerance limits. Or, sometimes, they just get lucky.”

In the southern U.S., research has already shown that some tree species are climbing the mountain slopes in response to a warming climate. Farther north, trees are invading arctic tundra. Will the zone of the “crooked wood” in the northeastern mountains move higher as well? The answer is . . . not necessarily, and no one knows.

Paleobotanical studies show that tree line in the Presidentials hasn’t shifted much in thousands of years, though there have been several significant climate swings over that time. The dwarfed fir and spruce at high elevations stayed put even as the conifers at lower elevations disappeared from and reappeared in the landscape.

Climate models are better at predicting temperature than moisture and precipitation, said Kimball. But warm air can hold more moisture, and that could mean “more icing events for the northeastern mountains, which in turn could maintain the current forest line or possibly cause it to even move downslope,” he said.

Discussion *