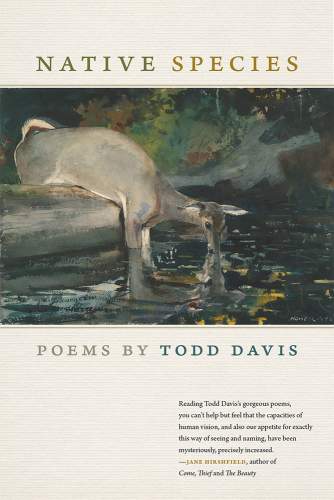

by Todd Davis

Michigan State University Press, 2019

When I venture into the woods – chainsaw on shoulders or skis strapped to boots – I assume that once I enter the natural world, my scattered brain will empty. I expect that worries about my daughter’s cold or building my shed will disappear. Sometimes they do. But just as often, with every step, my mind, rather than emptying, dances with ideas.

Todd Davis’s stunningly beautiful sixth book of poetry, Native Species, reminds me of this lesson. As the son of a veterinarian, Davis sees the natural world through a scientist’s eyes. Davis knows Latin names, common names, habitats, and habits. His poems are steeped in the exactness of the earth and the science that unfolds in wildness, which makes each of his poems a stunning portrait of a time and place. The reader is brought to trout streams, talus slopes, frozen lakes, and barbershops.

But these place-based poems aren’t just examinations of the natural (and, at times, human-constructed) world. They also explore the narrator’s thoughts on topics as varied as father-son relations, lust and love, politics, and jazz. In all of this, Davis – an award-winning poet from central Pennsylvania – shows the reader that when we venture into the world around us, our minds hike along with us.

In “Logjam on Lookout Creek,” the narrator explores a logjam, highlighting the beauty surrounding these entwined logs: “Stoneflies have hatched in this place of rest, / time-tempered, bent, and slowed by the sound / of creek bumping against pushed up gravel.” Then, surprisingly, the poem explodes into a metaphor for the current political climate, which has fashioned “failed dams / that momentarily change the course . . . on toward the cities of ruin.”

In “Coltrane Eclogue,” Davis compares the sounds of nature – “Where the beak of a pileated opened a row / of holes down the length of a snag / wind blows across each notch” – to jazz legend John Coltrane’s “Love Supreme,” hearing the woods’ song as “Saint Coltrane / unfastening pearl and brass, exhalation rushing through the neck of a saxophone.”

In “With Nothing Between Us and the End of the World,” Davis fishes alone on a creek: “A shadow swirls from between rocks as a trout rises.” While landing a trout, his mind leaves the creek and lights upon his wife, far away: “Even a few days separation hurts,” Davis writes. Back and forth, Davis takes us, creek to-wife-to-creek, until the two become married: “The fish swivels out of my hands, across the current, like you do after we make love.”

Davis’s poems radiate with life as he brings readers not just into the natural world but into the ideas that bubble up while we hike or fish or log. Davis reminds us that we “are connected to everything else” and that our minds do not empty in nature. They swell.